|

The ISP Column

A column on things Internet

|

|

|

|

|

NANOG 96

February 2026

Geoff Huston

If I learned one thing at NANOG 96 it's how to build an up-to-date state of the art AI data centre! As I now understand it, the process is quite simple: take everything that is at the raw bleeding edge of today's technology: a collection of some 60,000 advanced GPUs using 3nm silicon fabrication processes, 3D-stacked high bandwidth memory, massive amounts of power, capable of delivering some 150Kw to 200Kw per equipment rack, and a local power system capable of sustaining up to 100Mw of total power for the entire centre, equip every rack with a liquid cooling system, and provision each rack with power bus bars, and then mesh-connect the GPUs to both each other and high speed storage in a lossless connectivity mesh using 800G optics and high density switches. Obviously, all this is not cheap, so you're going to need substantial financial backing, as well as a massive amount of local community approvals, particularly if you want to be so bold as to try and use modular nuclear generators for power! And once you've done all that, then be prepared to build an even bigger one in 18 month's time, as most of the centre's parameters will have doubled!

>This is insane!

The computing industry has gone through major shifts from the monolithic shared mainframe computer to the widely distributed personal computers and then further in the direction of ubiquitous device-based mobile computing, and now the technology pendulum is swinging the other way to spend eye-watering sums of capital to build these monolithic AI data centres. If each data centre ends up consuming the electric power budget of small nation states, then I guess we are not going to end up with that many of them, but the race to position product into these centres is well and truly up and running in this industry! The only question left for me is have we reached peak "AIphoria" or is there even more rabid madness to come?

The common folklore about this wave of activity is that the risk of under-investing is significantly greater than the risk of over-investing, and at the very worst all that would result is that the industry has pre-built sufficient data centre capacity for the next 3 - 5 years. We are pouring money into this AI slop bucket at a rate that is quickly approaching trillions of dollars per year. Such sums of capital are not generated out of thin air, and at this point many other topics in the world of digital communications and networked services are taking a back seat. Security, privacy, resilience and service efficiency are still important topics in this realm, but in industry forums such as NANOG their collective consideration has largely deferred to AI infrastructure topics, at least for this most recent NANOG meeting.

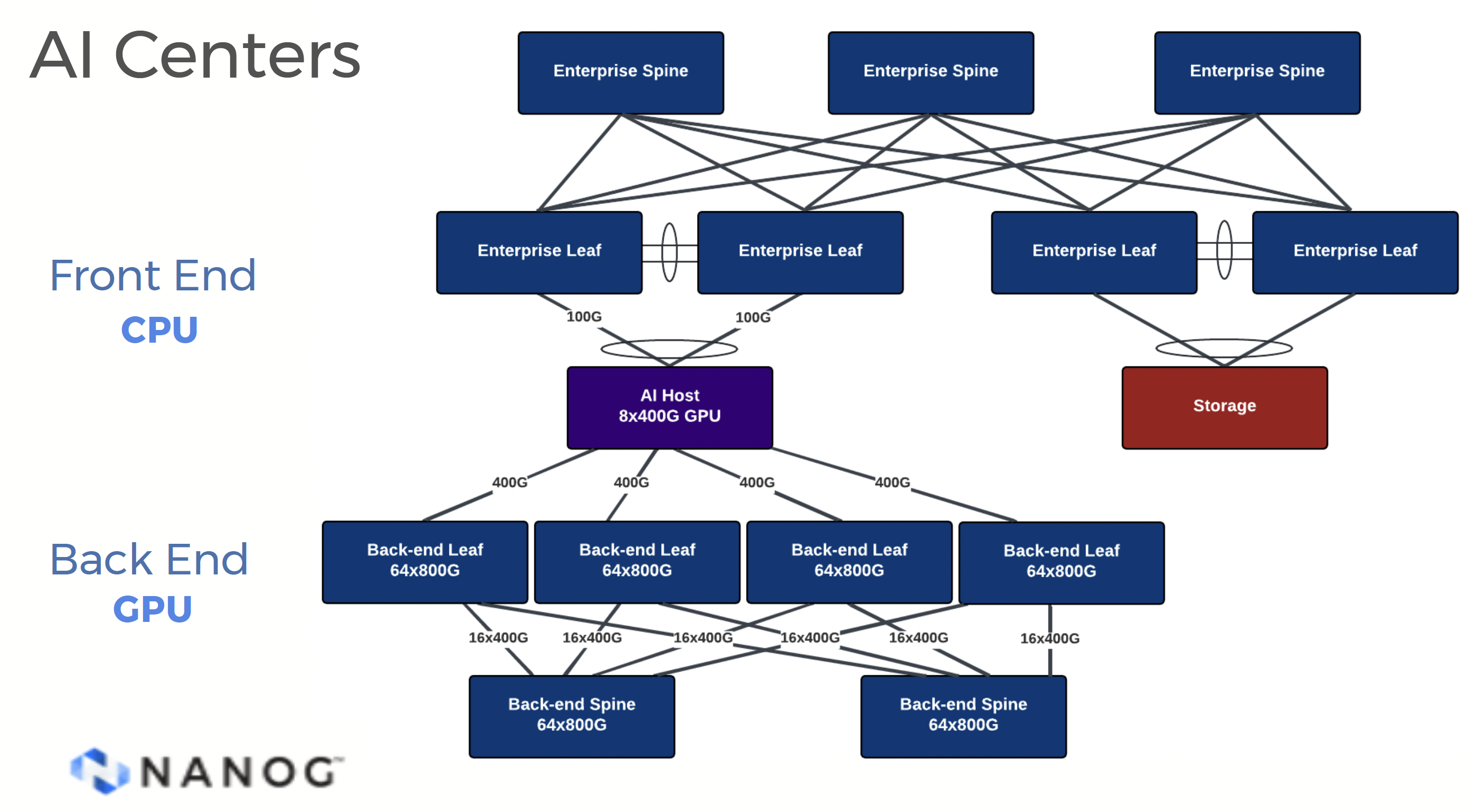

There is a substantial level of technology detail in this AI topic, as these facilities appear to be pushing the boundaries in every way. This is a case of assembling a swarm of GPUs, proving a front-end processing capability and mesh-connecting them to this collection of back-end GPUs. Of course we are not talking just one of two GPUs. Current leading examples of large-scale data centres, such as xAI's Colossus utilize somewhere between 200,000 to 555,000 GPUs in single-site installations. If you use 72 GPUs per track that’s a centre with between 3,000 to 8,000 racks. At 120Kw of power per rack that’s a grand total of up to a Gigawatt for such a centre. By comparison, the entire city of London is estimated to have a peak demand of 6 GW. Open AI's Stargate in Texas, XAI's Colossus in Tennessee, Meta's Hyperion in Louisiana and AWS' Project Ranier in Indiana are all examples of this ne generation Gigawatt-powered facility.

It's not only power requirements. From the data centre's perspective there is a need to provision these data centre processing hubs with unprecedented levels of demand for cooling and transmission capacity as well as power.

Figure 1 - AI Data Centre Architecture

Cooling can no longer rely on air movement to shed the heat generated within an equipment rack. Liquid cooling can dissipate heat up to 3,000 times more efficiently than airflow. With liquid cooling, at the very least, it's necessary to use liquid-cooled cold plates heat-bonded to the GPU chip to pull heat from these processing units and dispatch this heat in the form of heated liquid to the facility's cooling system. More extreme approaches involve the immersion of the processing units in a dielectric liquid (non-conductive oil). With platforms like NVIDIA's Grace-Blackwell GB200 NVL72 requiring up to 140kW of cooling per rack, large-scale liquid tub cooling is emerging as the only approach to support very large data centres constructed from such components.

Communications is also a demanding component of this effort. This is not a replication of current conventional data centre architectures where a collection of servers with local processing, memory and storage are interconnected to each other over an internal centre switching fabric and communicate externally to clients and remote servers. The GPUs in the AI Centre using the internal centre switching fabric to access memory as well as other processors. In many respects this communication network is the data centre analogy of the shared backplane of the old mainframe architectures. This imposes its own additional set of constraints. The communications protocol here is RoCEv2, or Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) over Ethernet using UDP. The most critical constraint is that all such communications need to be lossless, which is a high bar challenge when using a UDP transport which has no intrinsic loss detection and repair. A popular technology choice appears to be UltraEthernet or UEC, which is conventional Ethernet with a two-level prioritisation system (Priority Flow Control) and a form of Explicit Congestion Notification with probabilistic ECN intended to throttle senders at the early onset of queue bnuildup within the switch to avoid packet loss.

The internal communications environment in these AI Data Centres use a two-dimensional framework, where the "North/South" network provides the external interface, typically implemented as a 2 x 400 Gbps switched system, and an "East/West" network for data exchange between GPUs, typically implemented as an InfiniBand or UEC Ethernet at 8 x 800Gbps.

The industry is on a lavishly funded euphoric path to "build it!" without knowing what the limits are to build to, what the service model might be, and how the bills are to be paid and no clear idea of what "it" might be! It is fuelled by a mixture of the paradigm of the "winner take all" business model of the technology sector, coupled with a fear of missing out and some perception of an ill-defined threat to existing business models. In many ways it appears that whoever "wins" in all this is not necessarily first past the post, but whoever manages to outspend all the others! With the total construction bill now at an estimated 580 billion USD by the end of 2025, with much more to come in the near future, this now has all the features of a euphoric market bubble. Like all bubbles in the past, the next topic is when will this bubble burst, how intense will be the subsequent burst, and for how long.

Presentations:

- Beyond the Chip: The Unprecedented Infrastructure Demands of AI and HPC, Christopher Stewart, Ahead

- From Datacenter to AI Center, building the networks that build AI, Tyler Conrad, Arista

- AI Data Center Networking: Lessons from Meta's Evolution, Omar Baldonado, Meta

Onto other topics that were also presented at NANOG 96...

Netflix's BGP

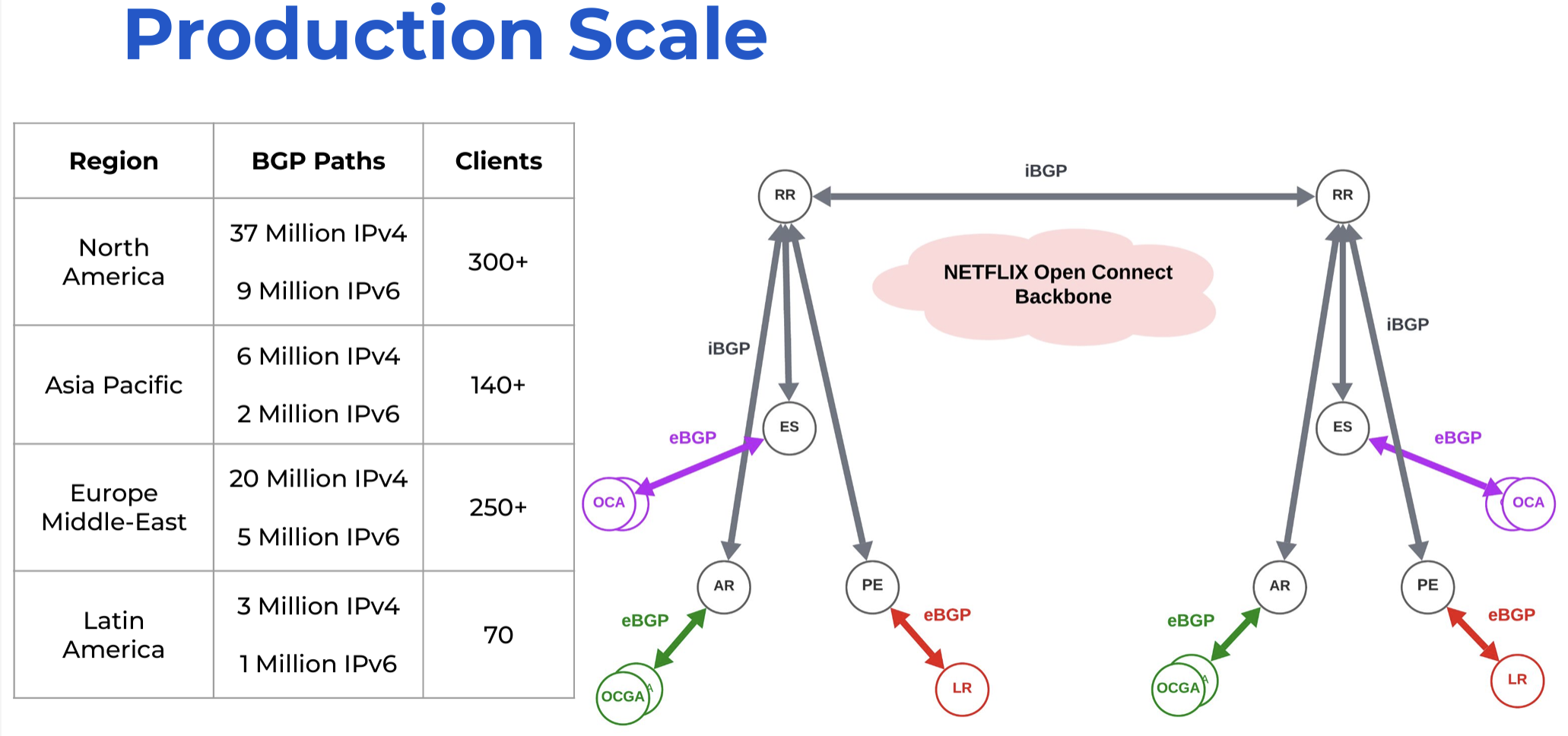

It perhaps goes without saying, but obviously Network is a major player in the content streaming sector at a global level. They deliver traffic to end users with an aggregate capacity of terrabits per second, operating some 19,000 Netflix Open Connect service appliances installed in IXPs and various ISP networks, across 175 countries. They operate some 400 PoPs, and in the routing system they xmanage some 20,000 eBGP sessions, peering with more than 2,000 different ASNs.

Their IP address holdings are relatively modest, as compared to the size and scope of their network. They announce some 228,864 IPv4 addresses from AS 2906 in some 213 distinct advertisements, and slightly less than a /30 in IPv6 in 237 prefix advertisements, and they use with a smaller ancillary network to connect their Open Connect appliances back into the Netflix core network.

It's a conventional BGP network, with Edge Switches, Aggregation Routers and Provider Edges, and they run a full iBGP mesh between Edge Switches and Provider Edges.

Full meshed connectivity does not scale well. N-squared is fine for 4 or 5 network elements, but by the time you get to a thousand or so it becomes a nightmare. For this reason, back in the very early days of BGP in 1996, the IETF published RFC 1996 ("BGP Route Reflection - An Alternative to full mesh IBGP"). The concept is relatively simple: each active BGP speaker connects to one or more BGP route reflectors, and passes the reflector all its updates as if it were a normal iBGP connection. When the route reflector receives an update, it passes it to all other iBGP-connected BGP speakers.

This Netflix presentation described the shift from a full-mesh iBGP environment to a Route Reflector approach. The design chosen by Netflix uses regional Route Reflectors for their BGP-speaking elements and cross-connecting these Route Reflectors. In many ways, it's all textbook-standard stuff without surprises or novel twists.

Frankly, it's hard to discern what, if anything, is novel in this story. The Netflix BGP network was suffering from growth pains due to the multiplicative pressures from operating a full internal mesh, and the logical answer was to migrate from full mesh iBGP to Route Reflectors. I guess the only question I have is "What took you so long?"

Figure 2 - Netflix Route Reflector Internal Design

Presentation:

Decentralizing Software Defined Networking (SDN)

The Internet has relied on dynamic routing protocols since its inception. The critical features of these protocols was firstly self-learning, so the protocol could dynamically discover the topology of the network and make sequences of forwarding decisions to deliver packets to their destination without external direction, and secondly self-healing, to dynamically discover when events disrupt that topology and automatically repair the topology to the extent that it's feasible.

At least that's what the original routing protocols were attempting to achieve, and they were largely successful in that endeavour. When I listen to a presentation about catastrophic failures in large scale routed systems I can't help but wonder: What went wrong in the evolutionary process of routing systems that has resulted in a routing system cannot reliably self-repair? Another way of looking at this is to wonder why routing systems regularly suffer catastrophic outages even though the larger system's design objectives for resilient dynamic routing are intended to render such scenarios infeasible.

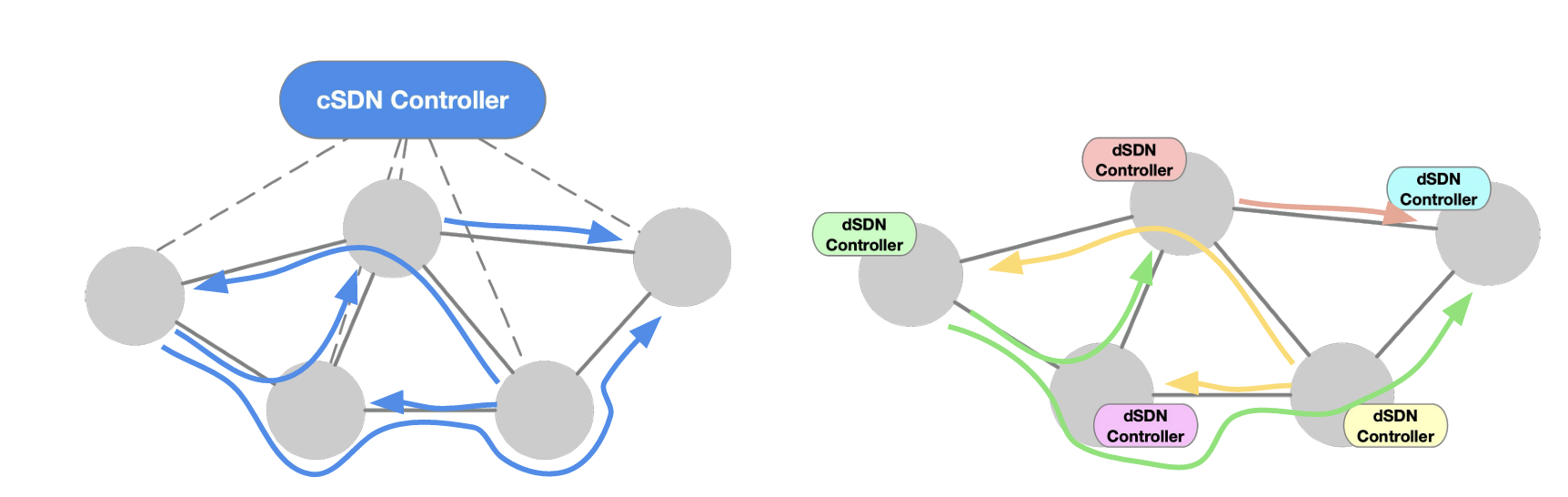

If I correctly interpret this presentation, it is asserted that the shift to SDN gave network operators the benefit of operator-defined code to override the outcomes of a conventional distributed routing protocol, directed traffic engineering and the simplicity of what is curiously termed “consensus-free” path selection. As far as I can see, there is an implicit assertion that path state forwarding in a network is somehow superior to a self-learning system. The issue with imposing path state in a hop-by-hop forwarding system is that its trusting in the future - when a controller makes a decision to include a router in its pre-computed path, then it's trusting that the local network state for that router remains constant. This is not exactly an approach that builds resilience.

A centralised SDN model has all network elements reporting their local link states to a controller, which then uses a combination of SPF and network-wide constraints to generate a set of paths and then communicate these path states back to the network elements. The decentralised SDN model proposed in this presentation performs the controller's path computation in code in each router. (Figure3)

Figure 3 – Decentralised SDN Framework

I must admit that I find it hard to understand how this decreases the essential operational fragility of path state forwarding. I suspect that the opposite is a more likely outcome.

Presentation:

IPv4 Address Movements

When various regional address policy fora decided to permit address trading, particularly for IPv4 address prefixes, it was a tacit admission that following the effective depletion of the unallocated address pools held by the RIRs, the only remaining way for addresses to be shifted to the parts of the network where there still need was to use market-based address transfers, and that's what the Internet industry has been doing for the past decade or so.

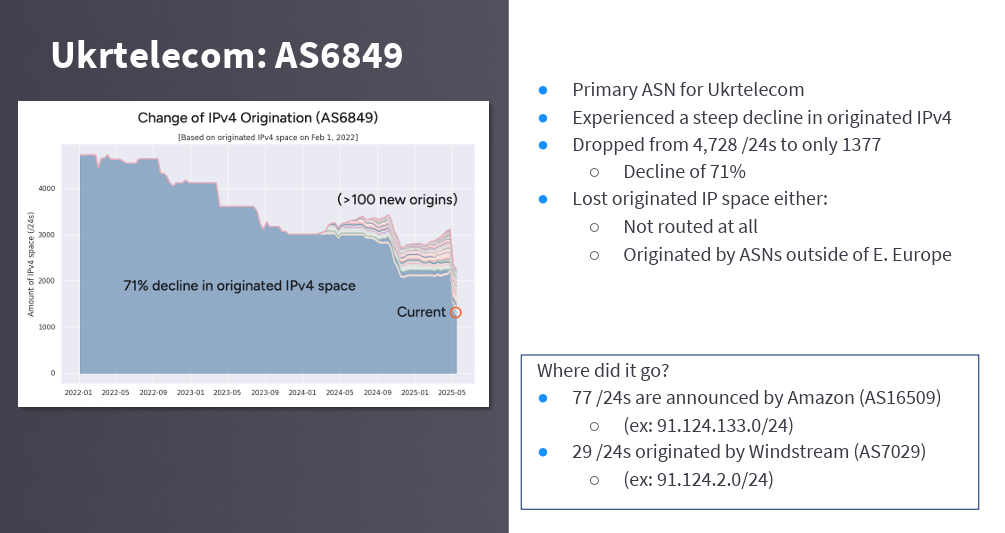

Doug Madory reported on his efforts of tracking of the movement of IPv4 addresses that were held by IPs in the Ukraine since 2022. The presentation noted that large amounts of IPv4 space, formerly originated by prominent Ukrainian network providers, have migrated out of the country, resulting in a 20% reduction in the Ukraine's footprint in the global routing table.

It's an interesting piece of research and the presentation used a good visualisation technique (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Visual Representation of Address Movement

This work also highlights an important aspect of registry data management, that it's not only important to have a comprehensive and accurate current picture of the current disposition of IP addresses today, but it's also important to maintain a log of the changes in the past that have contributed to the current picture.

Presentation:

RPKI Adoption

The effort to augment the Internet's inter-domain routing system with cryptographic credentials to permit routing systems to validate the authenticity of routing protocol updates has accumulated a rich history over the past three and a half he decades. This extended period is a testament to the difficulty of the task and the rich set of constraints within which the system must operate.

What we've arrived at is a three-part system, which is comprised of the generation of cryptographically-signed credentials, the flooding of these credentials to all BGP speakers, and the application of these credentials to locally held BGP data. These three components are inter-dependant, so it is just a partial picture of the situation when you look at just one part to the exclusion of the others.

Which is the case with the NANOG 96 presentation on "Removing Barriers to RPKI Adoption." The current situation at the start of 2026 has a little over one half of the advertised address space described by Route Origination Attestations.

It's relatively straightforward to examine a BGP routing table and extract the address prefix origination information and propose ROAs that match what is visible in the routing system, which appears to be the motivation behind the tool at https://ru-rpki-ready.iss.cc.gatech.edu/.

But there far more than ROA generation in the larger picture of securing routing. These cryptographic credentials need to be published in a manner that is readily accessible by all RPKI clients, and this data needs to be applied to BGP routing information in the client's BGP routers. We need all three elements of this framework for RPKI to work.

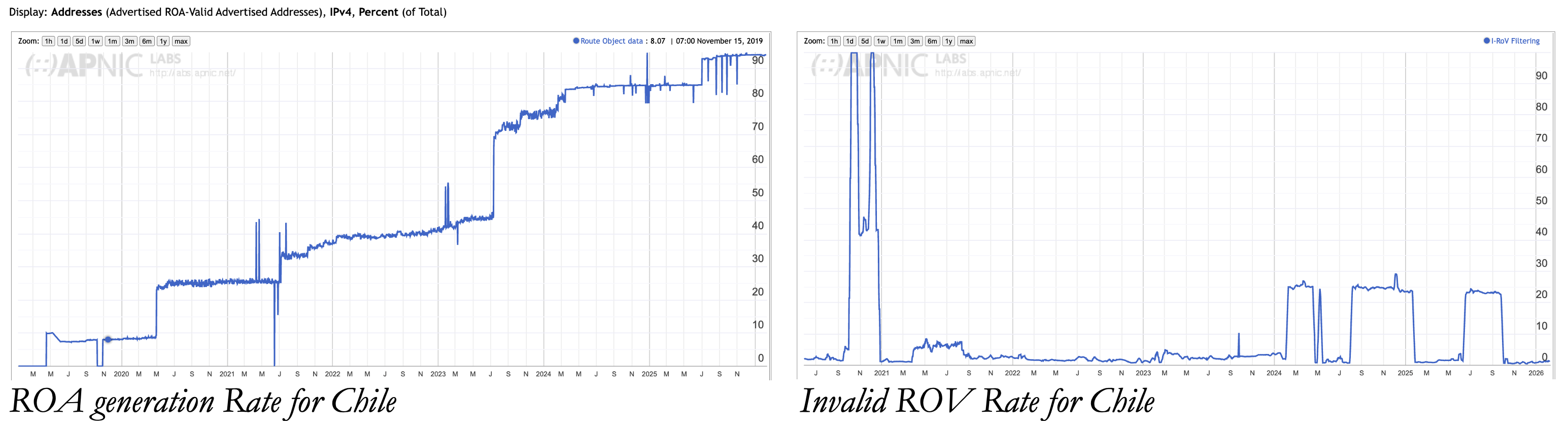

Just the production of ROAs is only a part of the story. In Chile, for example, some 85% of all advertised prefixes have associated ROAS, yet few service providers perform the dropping of prefixes that are ROA-invalid (Figure 5).

Figure 5- ROAs and ROV-Drop for Chile

It appears to be anomalous to orchestrate a large-scale effort on the part of a national community to generate these routing security credentials yet not deploy the router configuration that would enforce the outcomes validation of route objects using these credentials. One without the other is tantamount to wasted effort!

Perhaps the most frustrating part of all of this is that without any effort to protect the integrity of the AS path, a malicious routing attack can be readily mounted. As long as routing origination is preserved, it is possible to falsify an AS Path in a manner that is undetectable by ROAs. There is some hope that the long-awaited ASPA construct will play a vital role here, but it's hard to be optimistic given that the ASPA design choice of combining partial network topology with partial routing policy to come up with an ASPA was a broken design choice in the first place! If there is a perception that ROAs are challenging to manage, then the somewhat odd mix of partial topology and policy that is described in an ASPA object will challenge a far larger set of network operators.

At the moment, what we have built in the RPKI routing security framework is a rather complex and ornate artefact that at best can react to a subclass of route leaks and does little to protect the routing infrastructure against deliberate efforts to subvert it. I'm somewhat resigned to the conclusion that it may be many years before we are ready to tackle this subject again and try to craft some improvements to the routing security landscape, if at all. It's perhaps just as well that in todays last mile data centre-to-consumer Internet routing, and security of routing, just does not matter any more!

Presentation:

BMP

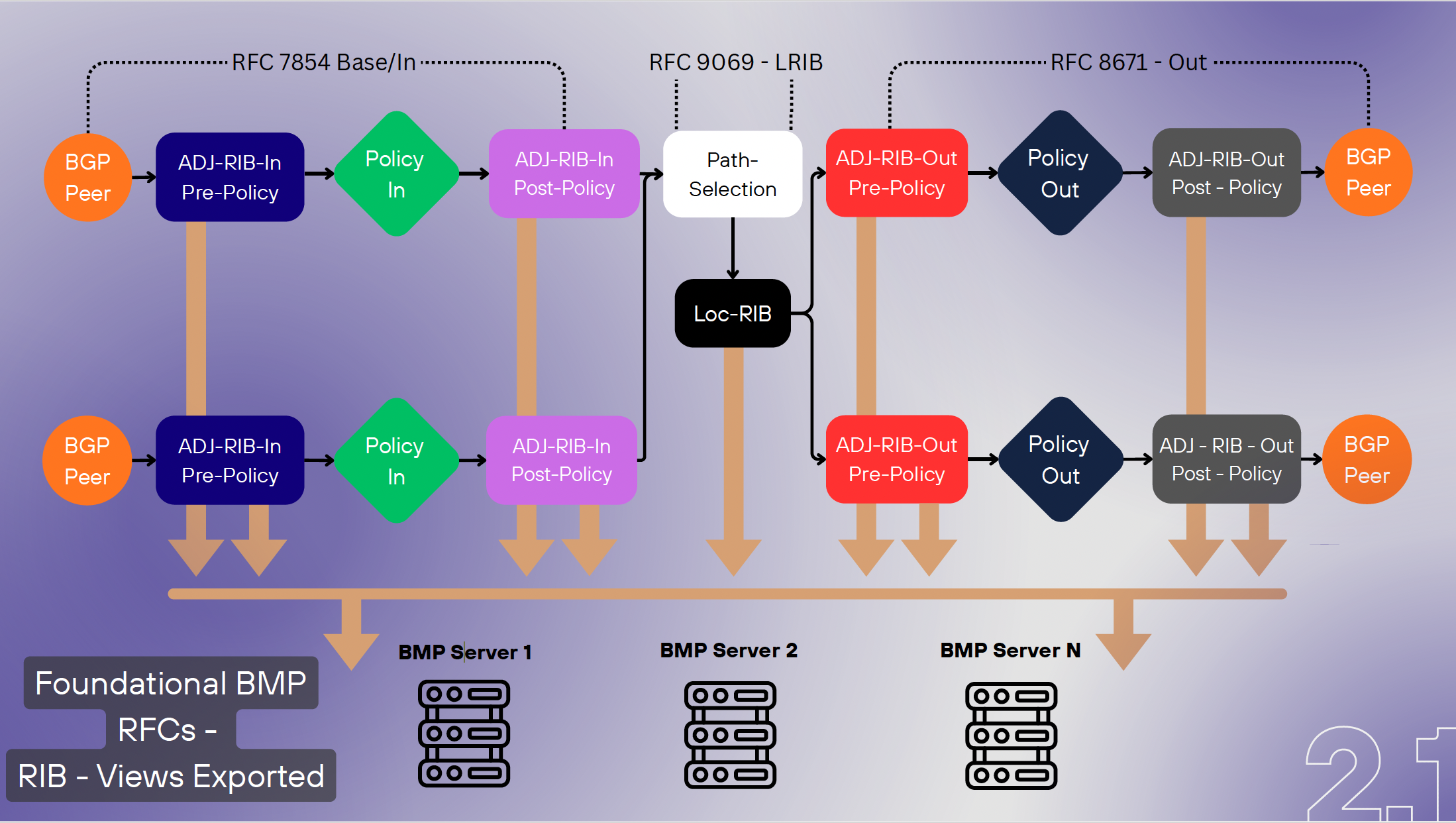

While on the topic of routing, it's interesting that the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is one of the few protocols that has stimulated the development of its own dedicated reporting protocol, the BGP monitoring Protocol (BMP). BMP's relatively widespread adoption and use points to the value of such a tool. The protocol is still under active development in the IETF, particularly as it relates to increasing the breadth of visibility in the operation of the BGP control engine and the input and output feeds to external peer BGP speakers.

BMP a distinct improvement from the prior way of generating information about BGP. This was to use an expect script to automate access to a BGP console and generate commands that collected live BGP information back from the console, or setting the BGP system into debug mode and generating an ascii dump of all BGP transactions. Another common technique was to set up an external BGP peer relationship and record all BGP messages, inferring the behaviour of the BGP system from these messages. BMP can directly expose this information without the need to perform indirect inference.

BMP exports a BGP speaker's control state with an associated metadata stream that provides a commentary on the local changes to control plane of the BGP system enabling data aggregation and centralized data collection tasks. BMP functions are aligned to the generic internal structure of a BGP engine, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6 - BMP and internal BGP System organisation

There is further work on BMP in the IETF in the area of defining Type Length Vector (TLV) codes to allow BMP to be extensible in terms of supported data types. There is now the capability to add BGP Best Path decision outcomes to mark a prefix and path with the status and reason. BMP's time handling has also improved to mark when a BGP state change triggered the event, and the time the BMP message was exported from the router.

There is also work on defining BMP over QUIC, which will be able to leverage QUIC support of multiple streams and its built-in TLS support. There is also work in defining BMP for monitoring RPKI.

Presentation:

Geofeeds

In the Internet of the 1980's computers were usually anchored to the floor of a dedicated computer room. It's location was fixed, as were the IP address it used, but at the time its location was of little interest. Over the decades were shrunk the end device to the point where the most prevalent attached device mobile, it has no fixed location, and its IP address is varying. Oddly enough it often has highly accurate location capability as any navigation app user can attest, but it this is not used for remote probing for the device's location. We use the device's IP address as a proxy for the device's location.

This is stupid.

These days devices are address-agile, and the scope of locality where a device might be when using a particular address ranges from the highly specific to an uncertainty range of the entire earth. For example, some aircraft inflight WiFi services use a fixed address for the duration of the flight, so there is absolutely no notion of a fixed location for the addresses used by these services.

But deriving a guessed location using IP address has three things going for it that have made it seductively attractive: its really, really cheap, it does not require user permission of any form, and it can be performed remotely without the user's awareness. Little wonder that the Digital Rights industry has glommed onto IP geolocation in a big way, despite the clear challenges with accuracy and the more insidious issues of personal privacy and informed consent when guess a user's location.

The early location maps were extremely cheap and extremely inaccurate. The common source was the address registries operated by the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) where the use of a two-letter country code in the registry was taken as an acceptable proxy for location. The content industry came to rely on this tool, despite its obvious issues, simply because the lack of an alternative. The mis-attribution of location manifested itself in many ways: the weather app displayed the weather for an entirely different location, the automated local language setting was totally absurd, or you could not access a movie, a your online, or access the right emergency service.

So we started to improve on the way an IP address location database was populated, using a common template for describing the location of an IP address (RFC 8805). The assumption was that you, or more likely your ISP, would maintain this location record, and the IP-to-location mapping services to provide a "better" location. Of course, you can't really tell if the location record publisher is trying to be helpful or deliberately deceptive in generating such a location record. So, we use RFC 9632 to use the RPKI to sign these records. They may still be deceptively false, but you can only lie about your own addresses! But it would not be 2026 unless we use AI slop to generate these location records for us! Because, as we all know, AI is infallible!

There are a number of geolocation provider services out there, and most use a model of aggregating these geolocation records, combining them with a core of RIR data, and providing a IP-to-location service. So are free, some are subscription services. Depending on the level of location specificity you are after, such services may be wildly incorrect, or just occasionally incorrect. Some geofeed record publishers just have no interest in disclosing their true location and will publish misleading records for that reason.

Some geolocation providers use ping and traceroute in an effort to place bounds of probability on an assertion of location, and there are other geofeed validation and geofeed aggregation websites.

Using IP addresses to establish a device's location is a pretty poor method. It can be coarse in terms of locational precision, its often gamed, and in many cases the information is completely unverifiable. On the other hand, its typically cheap and does not need explicit informed consent on the part of the end user. We end up using IP-based geolocation far more than perhaps we should.

Presentations:

- High-quality IP Geofeeds using AI Coding Assistants and MCP, Sid Mathur, Fastah

- IP Geofeeds: Trust, Accuracy, and Abuse, Calvin Ardi, IPinfo

Stuck Routes

BGP is a deliberately terse protocol. Once a peer has been informed of the reachability of an address prefix, it would not be informed again unless the reachability changed or the BGP session was reset. If a BGP engine loses an update, either by failing to correctly process an address prefix advertisement or a withdrawal, then the normal protocol action will not necessarily flag and repair such a situation.

From time to time someone performs a detailed examination of the routing tables in a router carrying a complete routing table, and the result is that they observe that the routing may be carrying a FIB entry that has been previously withdrawn by the BGP protocol, or is not carrying a FIB entry even though it has been advised of in an update. Such anomalies have been part of BGP since such detailed examinations first took place more than 30 years ago. They have been various termed "ghost routes" or "stuck routes". Such detailed examinations are challenging, and they occur infrequently. It is an open question to ask how many such stuck routes exist in today's routing table. Also, there are related questions as to how and where such stuck routes occur.

One approach to investigate stuck routes is to continually advertise and withdraw a small set of prefixes on a pre-determined schedule, so if a network is carrying a route that is not aligned with the schedule, then it's likely that this route has become "stuck".

We can take it a bit further by using a set of addresses and regularly cycle through the addresses. If you use IPv6 there are enough bits to encode the time of the announcement of the prefix in the prefix itself. There are theories about stuck routes that relate to a stuck TCP session.

It was noted there were cases with only 5% of a Tier 1’s downstreams seeing a route while it was in fact stuck there. The use of Route Reflector update groups or confederations or zones increase the complexity of detection, and sometimes it’s difficult to find the root cause even within an AS!

Presentation:

NANOG 96

The agenda for NANOG 96, including pointers to all sessions from this m,eeting can be found at: https://nanog.org/events/nanog-96/agenda/

In the near future the videos of these sessions will be posted to YouTube's NANOG channel; https://www.youtube.com/user/TeamNANOG

![]()

Disclaimer

The above views do not necessarily represent the views of the Asia Pacific Network Information Centre.

![]()

About the Author

GEOFF HUSTON AM B.Sc., M.Sc., is the Chief Scientist at APNIC, the Regional Internet Registry serving the Asia Pacific region.