|

The ISP Column

A column on things Internet

|

|

|

|

|

BGP in 2025

January 2026

Geoff Huston

At the start of each year, it’s been my practice to report on the behaviour of the Internet’s inter-domain routing system over the previous 12 months, looking in some detail at some metrics from the routing system that can show the essential shape and behaviour of the underlying interconnection fabric of the Internet.

The strong growth numbers that were a constant feature of the first thirty years of the Internet’s story are simply not present in the data in recent years. Is there is no more demand capacity to fuel further growth? Is the Internet losing its investment appeal along with so many other signals of investor disillusion over outlandish growth predictions in technology-based services? Has the massive transition into content distribution networks for digital services meant that there is a declining demand for the traditional form of content distribution over on-demand network access? Or has the current rush into generating ever more AI Slop simply drained all other activity sectors of capital investment and momentum? Or are consumer markets now so saturated that the Internet is no longer offering adequate growth potential for new investments? There is perhaps a more fundamental cause of this apparent slowdown of the Internet's growth. The past fifty years have been driven by the prodigious bounty of Moore's Law in the fabrication of silicon chips. Each year the current set of chips contained more gates while the fabrication costs remained relatively constant. The power of available computation capacity was doubling every 18 months or so, while the unit cost was halving at a similar rate. For a technology-based enterprise it was not an option to simply stand still: Potential competitors entering the market at later date had an inherent advantage in access to greater computation and storage capacity at a lower price. Incumbents needed to actively expand their market position and constantly refresh their technology base in order to simply survive. Such pressures are waning as the silicon chip industry confronts issues of basic physics in trying to generate chips with greater gate density with even lower power consumption at lower unit costs per gate. It's likely that we see further innovation in silicon chips, but at a far slower pace that we've become accustomed to, and perhaps at constant or even higher unit cost per gate. The pressures on incumbent service providers to continually expand their base in order to simply maintain their current market position is reducing, and this technology shift is now reflected in the metrics of the internal infrastructure of the Internet.

Let’s take a look at the Internet of 2025 through the lens of the inter-domain routing environment, and see how these larger technical and economic considerations are reflected in the behaviour of the Internet’s inter-domain routing system.

One reason why we are interested in the behaviour of the routing system is that at its heart the routing system has no natural self-constraint. Our collective unease about routing relates to a potential scenario where every network decides to disaggregate their prefixes and announce only the most specific prefixes, or where every network applies routing configurations that are inherently unstable, and the routing system rapidly reverts into oscillating between unstable states that generate an overwhelming stream of routing updates into the inter-domain routing space. In such scenarios, the routing protocol we use, the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), will not help us by attempting to damp down such behaviour. Indeed, there is a very real prospect that in such scenarios the protocol behaviour of BGP could well amplify the situation!

BGP is an instance of a Bellman-Ford distance vector routing algorithm. This algorithm allows a collection of connected devices (BGP speakers) to each learn the relative topology of the connecting network. The basic approach of this algorithm is very simple: Each BGP speaker tells all its other adjacent neighbours about what it has learned if the newly learned information alters the local view of the network.

Each time an adjacent BGP neighbour informs a BGP speaker about a change of reachability for an IP address prefix, the BGP speaker compares this new reachability information against its stored knowledge that was gained from previous announcements from other neighbours. If this new reachability information describes a better network path to the prefix, then the local speaker stores this prefix and associated next-hop forwarding decision into the local forwarding table and then informs all its adjacent neighbours of this new path to the prefix, implicitly citing itself as the next hop. In addition, there is a withdrawal mechanism. When a BGP speaker receives a withdrawal for a prefix from an adjacent neighbour, it stores the neighbour's withdrawal. If this withdrawn route happened to be the currently preferred route for this prefix, then the BGP speaker will examine its other per-neighbour data sets to determine which, if any, stored announcements represents the best path from those that are still extant. If it can find such an alternative path, it will copy this into its local forwarding table and announce this new preferred path to all its BGP neighbours. If there is no such alternative path, it will announce a withdrawal to its neighbours, indicating that it no longer can reach this prefix.

And that’s the two paragraph summary of BGP.

The first metric of interest is the size of the routing tables. Each router needs to store a local database of all prefixes announced by each routing peer. In addition, conventional routing design places a complete set of best paths into each line card and performs a lookup into this forwarding data structure for each packet. This represents an extremely challenging silicon design problem. The larger the routing search space, the more challenging the problem!

Why does memory size matter for a router?

If you look at the internals of a high-speed Internet router operating the default-free zone of the Internet one of the more critical performance aspects of the unit is to make a forwarding decision for each packet within the mean inter-packet arrival time, and preferably within the inter-arrival time of minimum-sized IP packets.

A router line card with an aggregate line rate across all of its serial interfaces of some 10Tbps (which is probably not a large capacity by today’s standards) needs to process each packet within 70 nanoseconds, assuming that the average packet size is 900 octets). If the average memory access cycle time is 10ns then this implies that the router line card processor needs to scan the entire decision space within just 7 memory access operations just to keep pace with the anticipated peak packet rate. A densely packed binary tree with 1M entries will require an average of 20 decisions when using conventional serial binary decision logic, so it’s clear that some other decision approach is needed here. These very high-speed decision tables are often implemented using content-addressable memory to bypass this serial decision limitation. Ternary content-addressable memory (TCAM) can search its entire contents in a single memory cycle. It’s fast, but it’s also a very expensive component of a high-speed router line card.

TCAM size is what you purchase when you buy the router, so you need to pay attention to not only what you need today, but what you may need over the operational lifetime of the unit. If the router is to be useful in, say, 5 years from now, then you need to deploy units that can maintain their switching performance levels five years from now. That often implies configuring your units with sufficient TCAM memory to contain IPv4 and IPv6 routing tables that are not only adequate for today but are adequate to meet the routing table requirements some years into the future. Getting it wrong means that you’ve spent too much on your switching equipment if you over-provision or are forced to retire the equipment prematurely if you under-provision. What this means is this size question is an important question both to network operators and to designers and vendors of network switching equipment.There is also the consideration of the overall stability of the system. Processing a routing update requires several lookups into local data structures as well as local processing steps. Each router has a finite capacity to process updates, and once the update rate exceeds this local processing capability, then the router will start to queue up unprocessed updates. In the worst case, the router will start to lag in real-time, so that the information a BGP speaker is propagating reflects a past local topology, not necessarily the current local topology. If this lag continues, then at some point unprocessed updates may be dropped from the queue. BGP has no inherent periodic refresh capability, so when information is dropped, then the router and its neighbours fall out of sync with the network topology. At its most benign, the router will advertise "ghost" routes where the prefix is no longer reachable, yet the out-of-sync router will continue to advertise reachability. At its worst, the router will set up a loop condition and as traffic enters the loop it will continue to circulate through the loop until the packet’s TTL expires. This may cause saturation of the underlying transmission system and trigger further outages which, in turn, may add to the routing load.

The two critical metrics we are interested in are the size of the routing space and its level of updates, or churn. Here we will look at the first of these metrics, the size of the routing space, and the changes that occurred through 2024, and use this data to extrapolate forward and look at 5-year projections for the size of the routing table in both IPv4 and IPv6.

The BGP Measurement Environment

In trying to analyse long baseline data series the ideal approach is to keep as much of the local data gathering environment as stable as possible. In this way, the changes that occur in the collected data reflect changes in the larger environment, as distinct from changes in the local configuration of the data collection equipment.

The major measurement point being used here is a BGP speaker configured within AS 131072. This network generates no traffic and originates no routes in BGP. It’s a passive network that has a single BGP speaker that been logging all received BGP updates since 2007. The router is fed with a default-free BGP feed from AS 4608, which is the APNIC network located in Australia, and AS 4777, which is the APNIC network located in Japan, for both IPv4 and IPv6 routes.

There is also no internal routing (iBGP) component in this measurement setup. While it has been asserted at various times over the years that iBGP is a major contributor to BGP scalability concerns in BGP, the consideration here in trying to quantify this assertion is that there is no "standard" iBGP configuration, as each network has its own rather unique configuration of Route Reflectors and iBGP peers. This makes it hard to generate a "typical" iBGP load profile, let alone analyse the general trends in iBGP update loads over time.

In this study, the scope of attention is limited to a simple eBGP configuration that is likely to be found as a stub AS at the edge of the Internet. This AS is not an upstream for any third party, it has no transit role, and does not have a large set of BGP peers. It's a simple view of the routing world that I see when I sit at an edge of the Internet. Like all BGP views, it is totally unique to this network, and every other network will see a slightly different Internet with different metrics. However, the behaviour seen by this stub network at the edge of the Internet is probably similar to most other stub networks at the edge of the Internet. While the fine details may differ, the overall picture is probably much the same. This BGP view is both unique and typical at the same time.

To complement this single view of the BGP network we will use the resources of two large route collector systems. We use RouteViews, a project supported by the Network Startup Resource Center (NSRC) at the University of Oregon. RouteViews has also enjoyed significant levels of support from the National Science Foundation and numerous industry entities. This route collector has been in operation continuously since 1997 and holds much of the routing history of the Internet in its archives.

The RouteViews Project was originally intended to offer a multi-perspective real-time view of the inter-domain routing system, allowing network operators to examine the current visibility of route objects from various points in the inter-domain topology. What makes RouteViews so unique is that it archives these routing tables every two hours and has done so for more than two decades. Their system also archives every BGP update message to complement the regular snapshot of the routing information base (RIB). This vast collection of data is a valuable research data trove.

The folk at the RouteViews Project, operated with the support from the Network Startup Resource Center (NSRC) at the University of Oregon and the US National Science Foundation and a number of other corporate supporters should be commended for their efforts here. This is a very unique data set if you are interested in understanding the evolution of the Internet over the years.

We also use the Routing Information Service (RIS), operated by the RIPE NCC. This service is operated by the RIPE Network Coordination Centre, the Regional Internet Registry for Europe, Middle East and Central Asia. Similarly to RouteViews, RIS operates 27 route collectors located across a diverse collection of locations.

There are currently some 777 BGP sessions that are being collected across all routing peers of these two route collector systems, with 398 route sessions providing an IPv4 routing table, and 379 IPv6 sessions.

The IPv4 Routing Table

Measurements of the size of the routing table have been taken regularly since the start of 1988, roughly coinciding with the early days of the NSFNET in the United States.

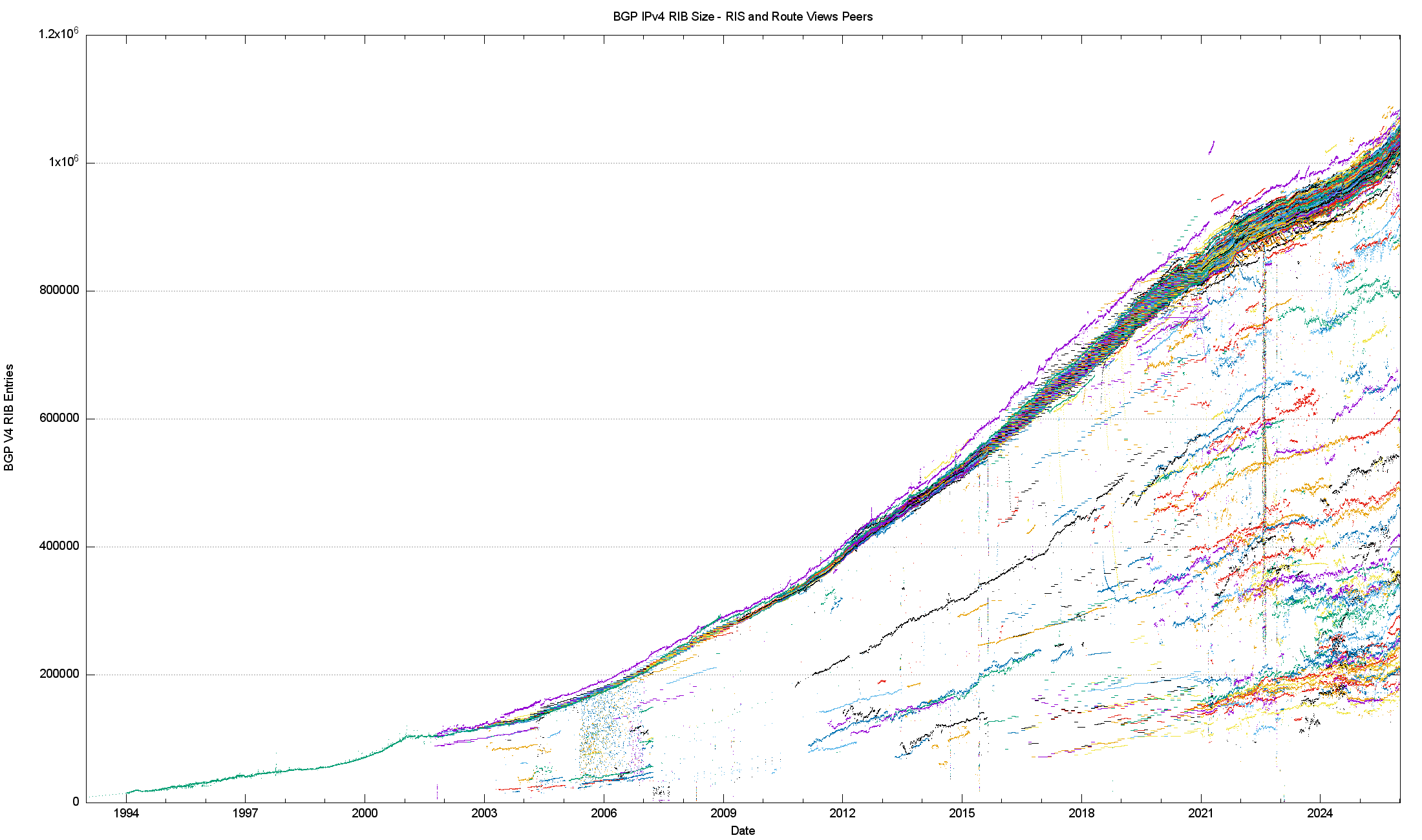

Figure 1 shows a rather unique picture of the size of the routing table, as seen by all the peers of the RouteViews route collector system and the RIPE RIS, since 1994.

Figure 1 – IPv4 routing table since 1994 as seen by RouteViews and RIS BGP peers

Several events are visible in this rendition of the history of the routing table, such as the bursting of the Internet bubble in 2001, the impact of the global financial crisis in 2009 and the lingering effects of the Covid-related shutdowns in late 2020. What is perhaps surprising is one ongoing event that is not visible in this plot. Since 2011 the supply of IPv4 addresses has been progressively constrained as the unassigned address pools of the various Regional Internet Registries have been exhausted. Yet there is no visible impact on the rate of growth of the number of announced prefixes in the global routing system since 2011. In terms of the size of the routing table, it’s as if the exhaustion of IPv4 addresses has not happened at all for the ensuring decade! It is only in the period 2021 through 2024 that we see some tapering of the growth of the size of the IPv4 routing table, but it now appears that this was a temporary hiatus, as over 2025 the routing table resumed its earlier pace of growth.

BGP is not just a reachability protocol. Network operators can manipulate traffic paths using selective advertisement of more specific addresses, allowing BGP to be used as a traffic engineering tool. These more specific advertisements often have a restricted propagation. This is evident in Figure 1, where there is no single plot in this figure. There is a variance in the total number of observed prefixes across the total of 1,026 peers of these two route collector systems that is around 50,000 routes.

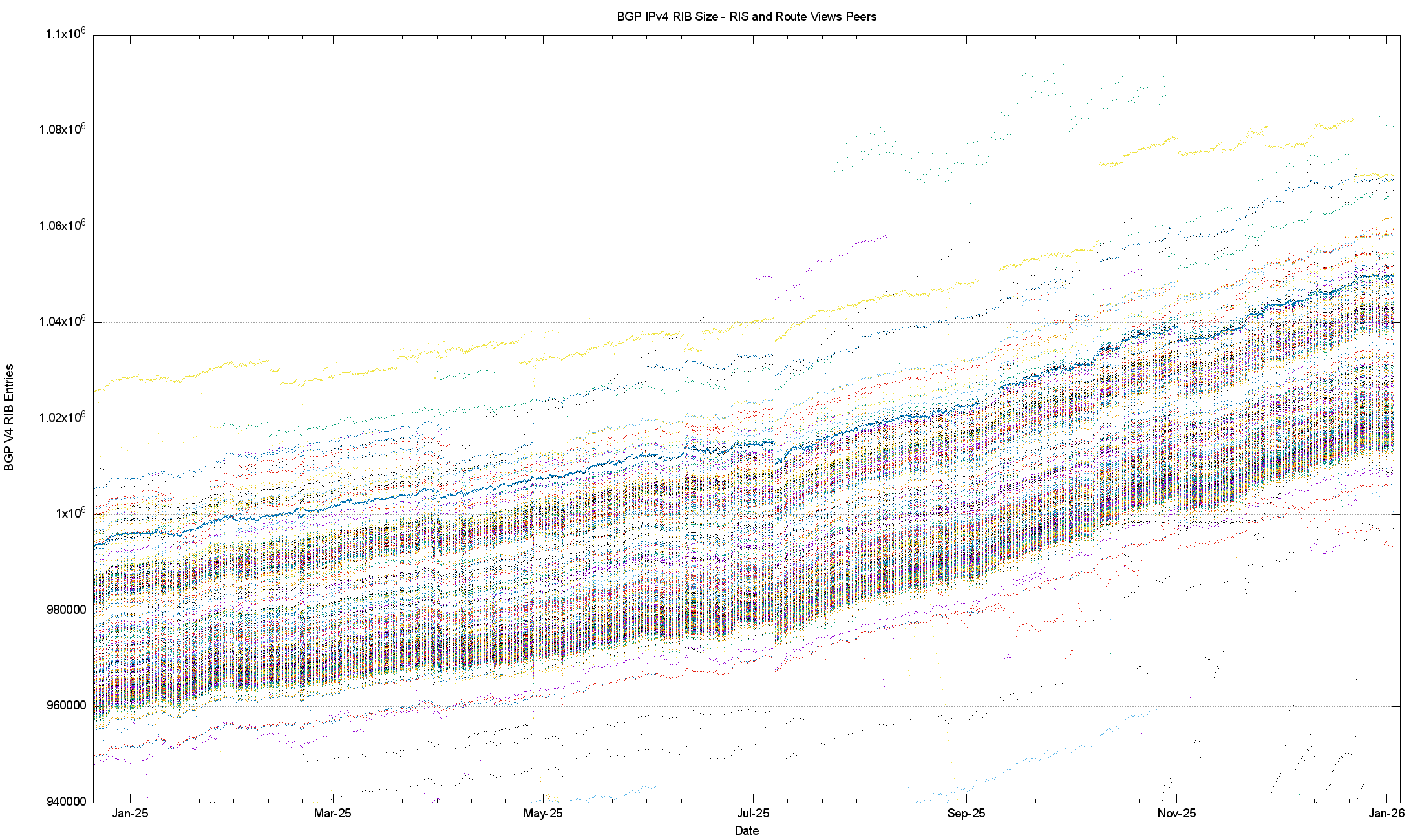

We can zoom in to look at just 2025, taking this same collection of RouteViews and RIS BGP peers (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – IPv4 routing table 2019-2024, as seen by RouteViews and RIS peers

Both Figures 1 and 2 illustrate an important principle in BGP, that there is no single authoritative view of the Internet’s inter-domain routing table, as all views are relative to the perspective of each BGP speaker. These figures also illustrate that at times the cause of changes in routing is not necessarily a change at the point of origination of the route which would be visible to all BGP speakers across the entire Internet, but it may be a change in transit arrangements within the interior of the network that may expose, or hide, collections of routes to a subset of the network's BGP speakers.

The issue of the collective management of the routing system can be seen as an example of the condition of the "tragedy of the commons", where the self-interest of one actor in attempting to minimise its transit service costs becomes an incremental cost in the total routing load that is borne by other actors. To quote the Wikipedia article on this topic “In absence of enlightened self-interest, some form of authority or federation is needed to solve the collective action problem.” This appears to be the case in the behaviour of the routing system, where there is an extensive reliance on enlightened self-interest to be conservative in one’s own announcements.

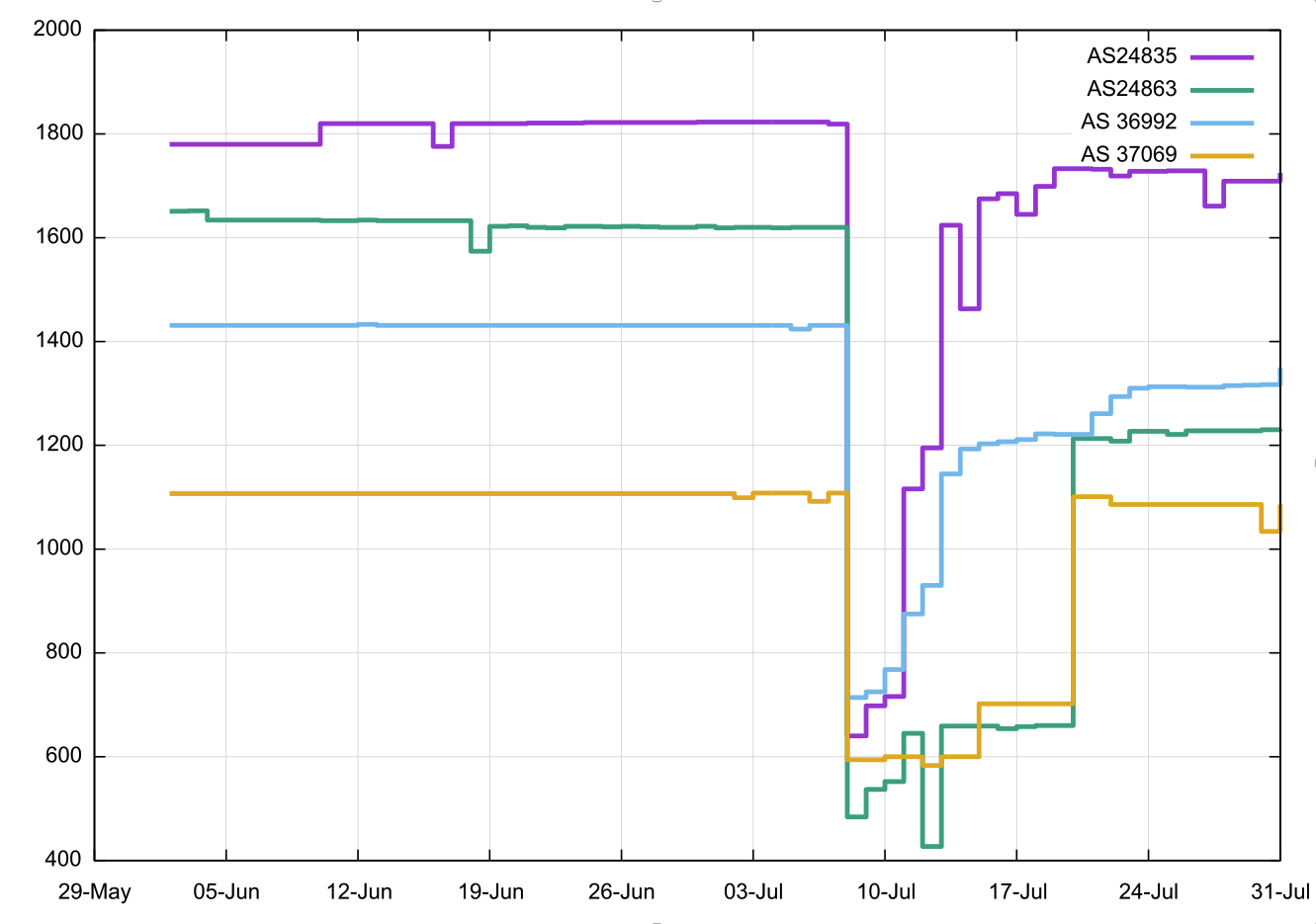

There are a couple of distinct discontinuities in Figure 2 which are observed by all BGP peers. On 1 November AS4155, the network operated by the US Department of Agriculture (the domain USDA.gov) withdrew 3,122 IPv4 advertised prefixes. These were all more specific prefixes with a total span of 965,000 address, and the result of their cleanup of their BGP profile was that on 2 November AS4155 advertised just 23 prefixes, covering a total span of 3.1M addresses. There was another routing anomaly on 7 July 2025. This was attributed to four networks located in Egypt (Figure 3).

\

Figure 3 – IPv4 routing anomaly in Egypt, 7 July 2025

On July 7, 2025, a major fire broke out at the Ramses Central building in Cairo, a critical telecommunications hub for the country. The fire resulted in four deaths, and significant disruptions to Egypt's internet and telecommunications services. The incident also led to a temporary suspension of trading on the Cairo stock exchange and caused severe traffic congestion due to street closures.

The next collection of plots (Figures 4 through 13) contains some of the vital characteristics for the IPv4 BGP network since the start of 2020 to the start of 2026, using the routing data for a single BGP session, collected from AS 131072.

| ||

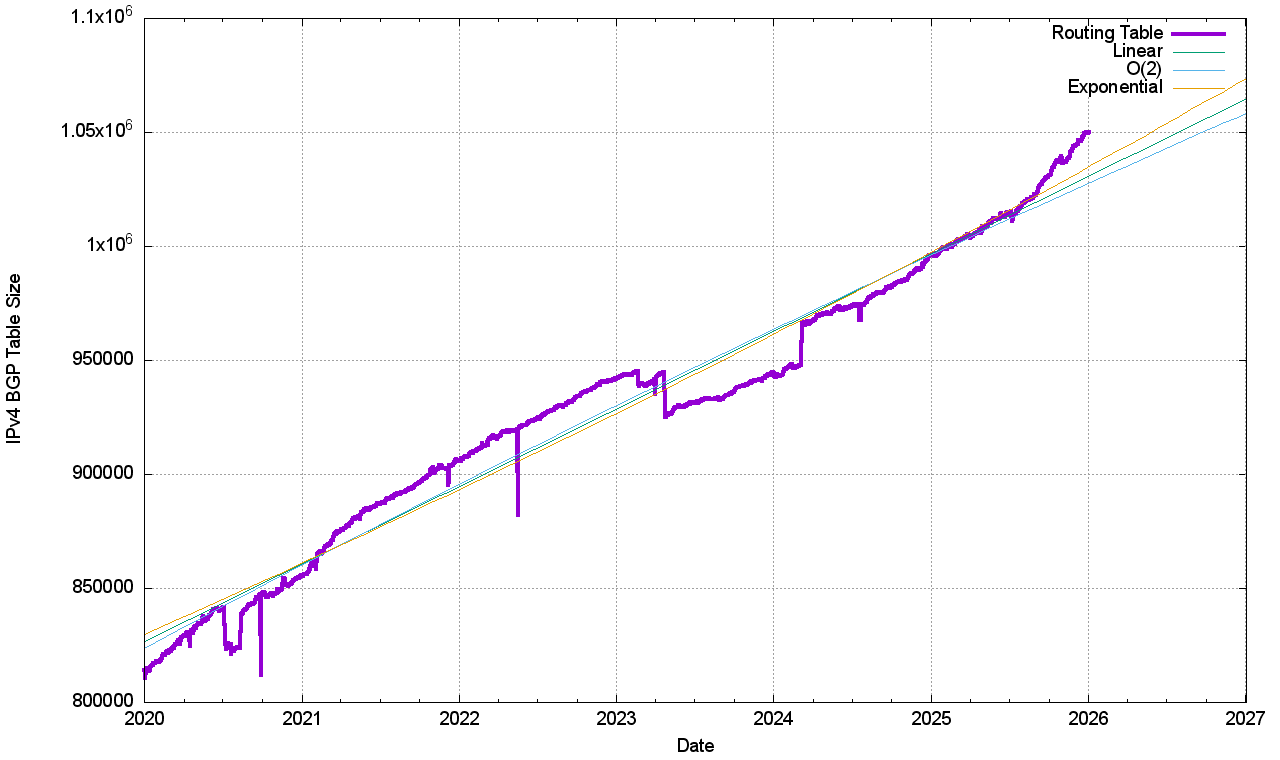

Figure 4 shows the total number of routes in the routing table over this period. The routing table has continued to grow, largely as a result of the advertisement of more specifics.

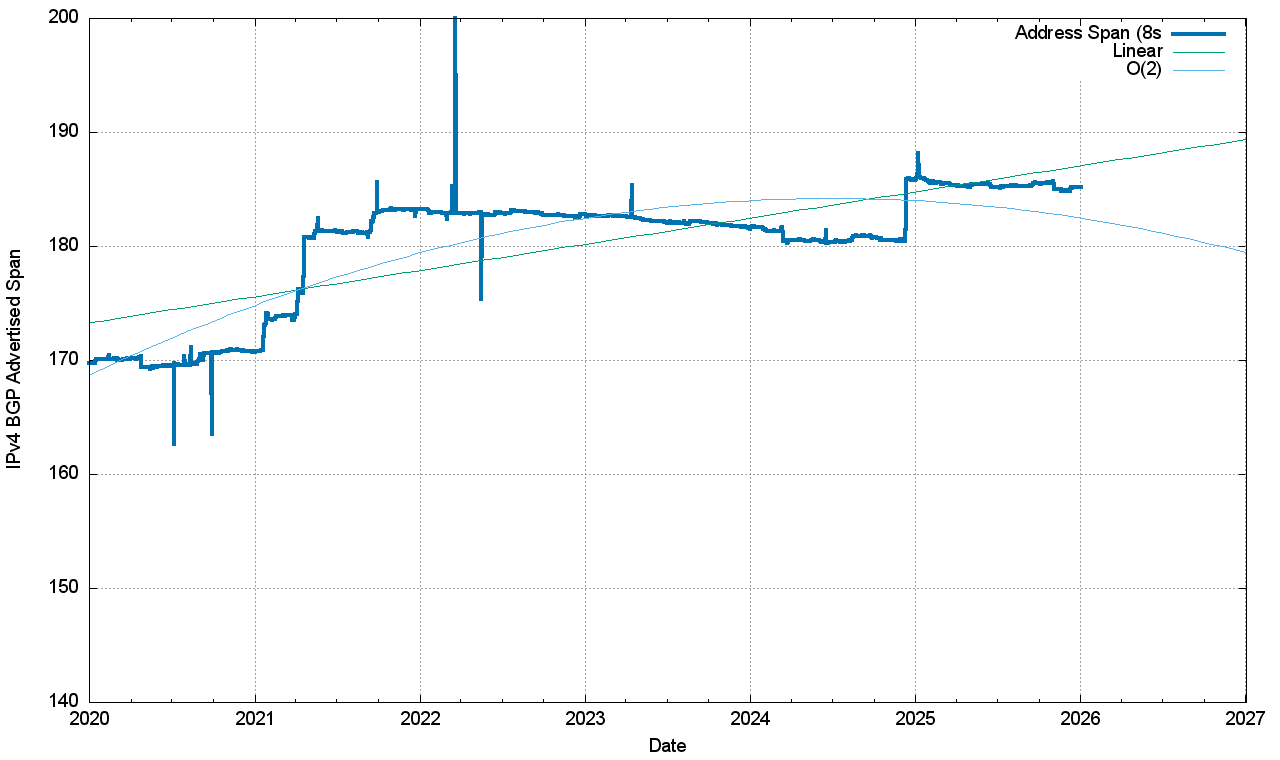

In 2021 we saw a number of large address blocks being advertised in the routing system by agencies associated with the US Department of Defence (Figure 5). Across 2022 and 2023 the total span of advertised IPv4 addresses declined. There was a sharp rise in the total span of address space on the 12th December 2024, coinciding with the advertisement of a total span of 81,224,704 addresses (the equivalent of 4.8 /8s) by ASes operated by Amazon. Their major network, AS16509, announced a span of 154,961,152 addresses at the end of 2025, or some 4.97% of the total IPv4 announced address span, second only to the 224,851,712 addresses announced by AS749 for the US Department of Defence. The collection of Amazon ASes collectively announces a span of 157,565,440 addresses at the end of 2025.

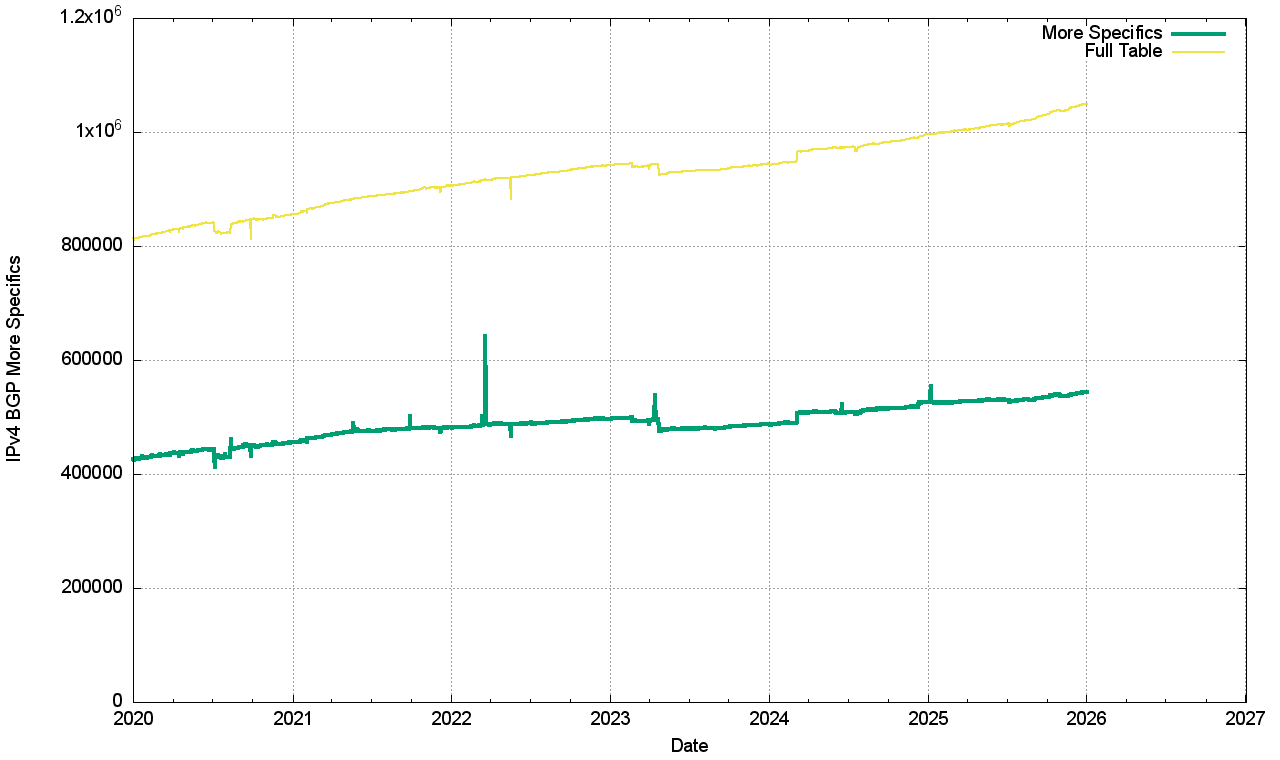

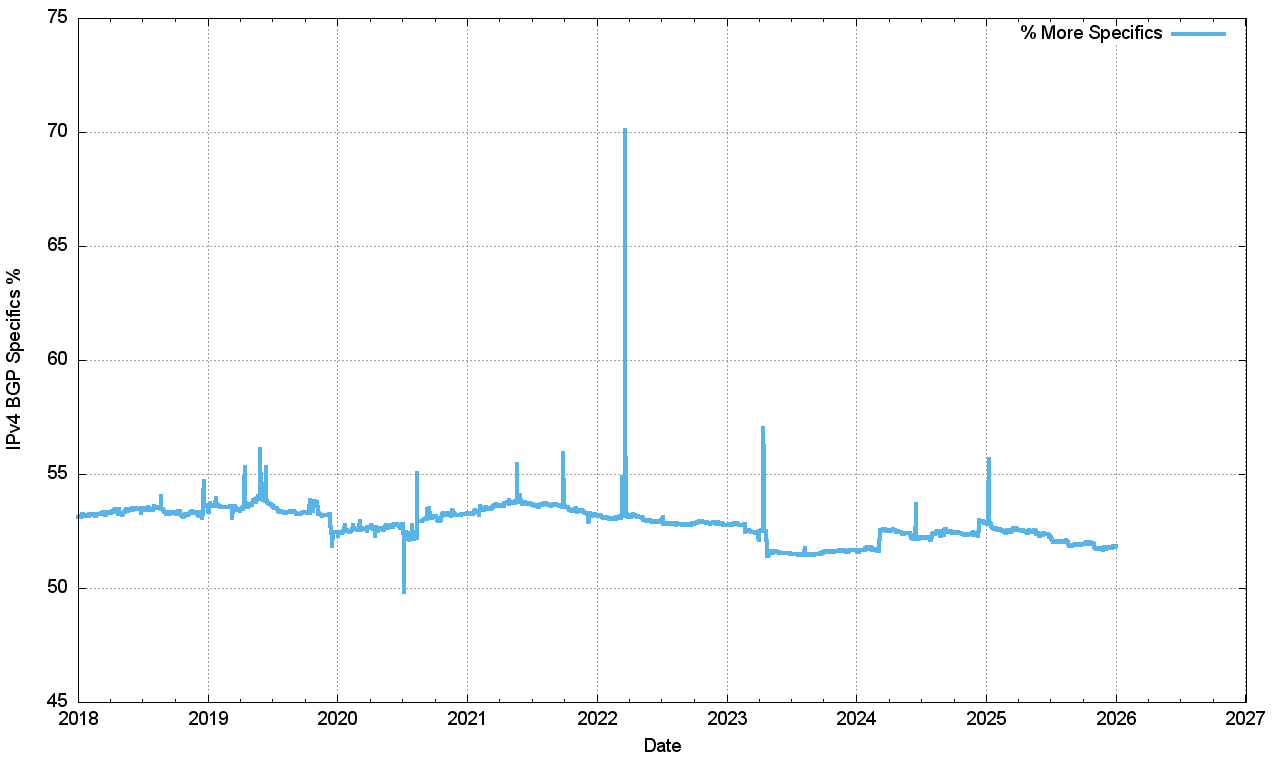

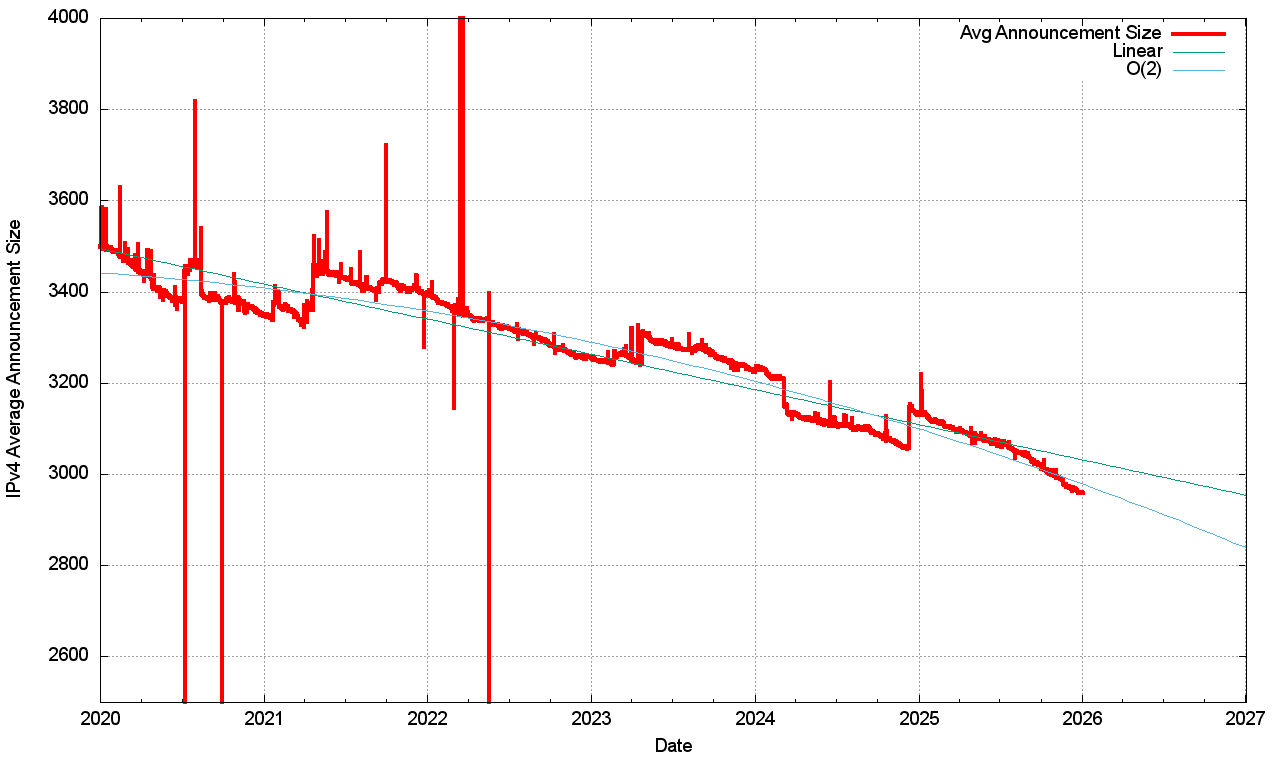

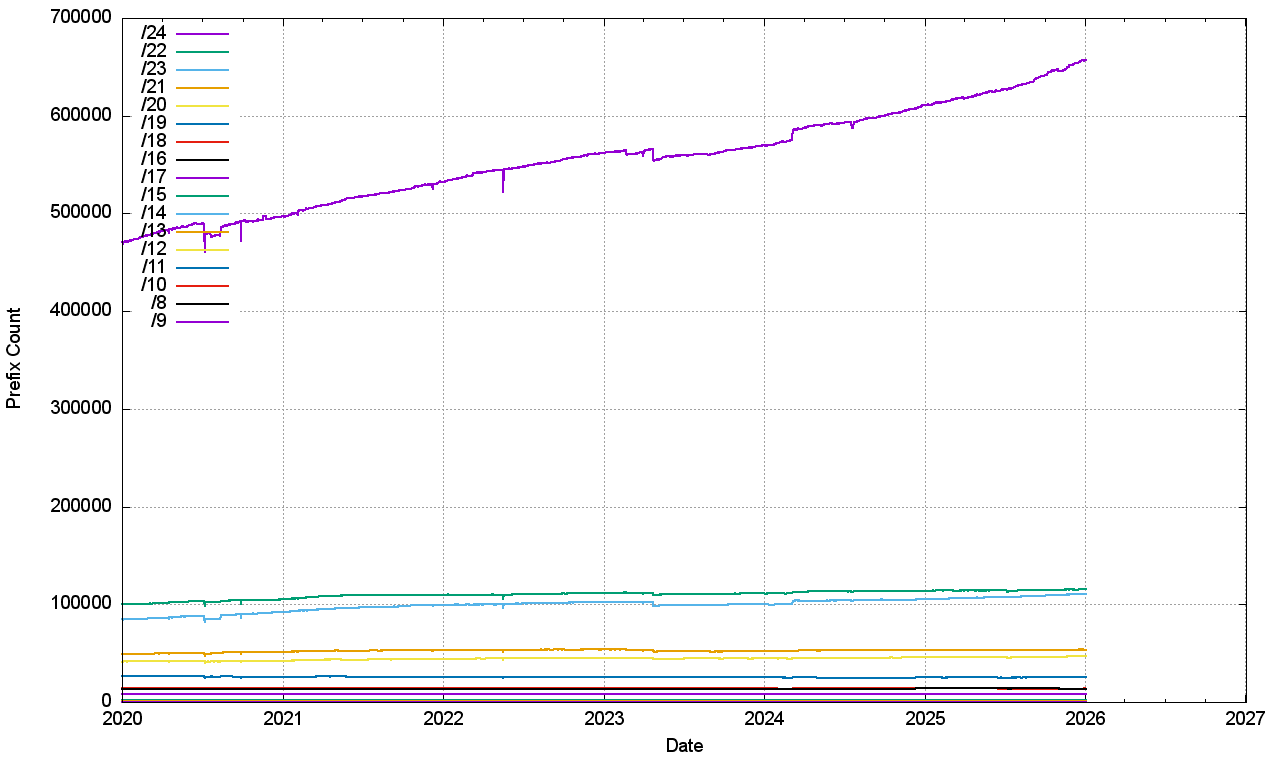

In terms of more specific advertisements and covering aggregate advertisements (Figure 6), the number of covering aggregate announcements increased across 2025 at a slightly greater than the increase in the number of more specifics. Looking at the ratio of these two counts, the ratio has declined slightly over 2025 (Figure 7). The average prefix size is now somewhat smaller than a /20 (Figure 8). Prefixes sizes of /24, /23 and /22 in total now account for 84% of the entire IPv4 routing table at the end of 2025 (Figure 9).

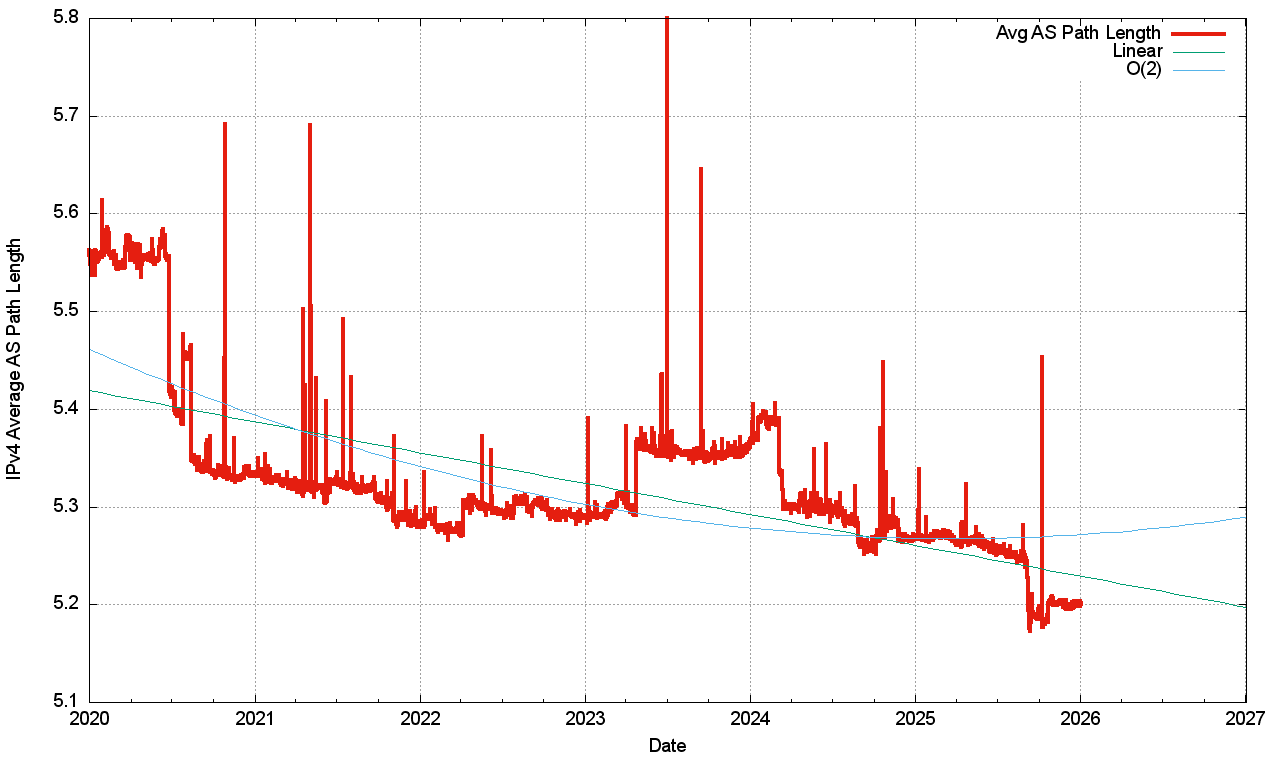

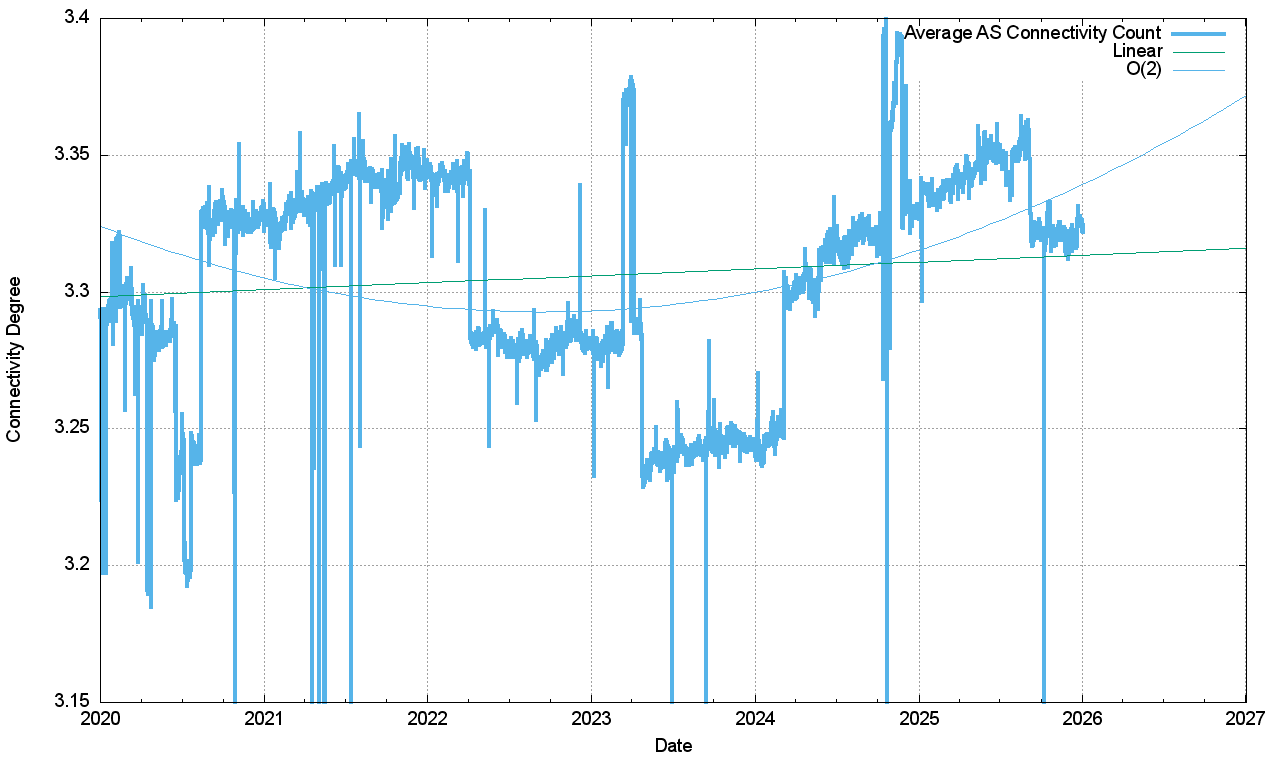

The topology of the network continues a trend to increasing centrality, with average AS Path length further decreasing through the year (Figure 10).

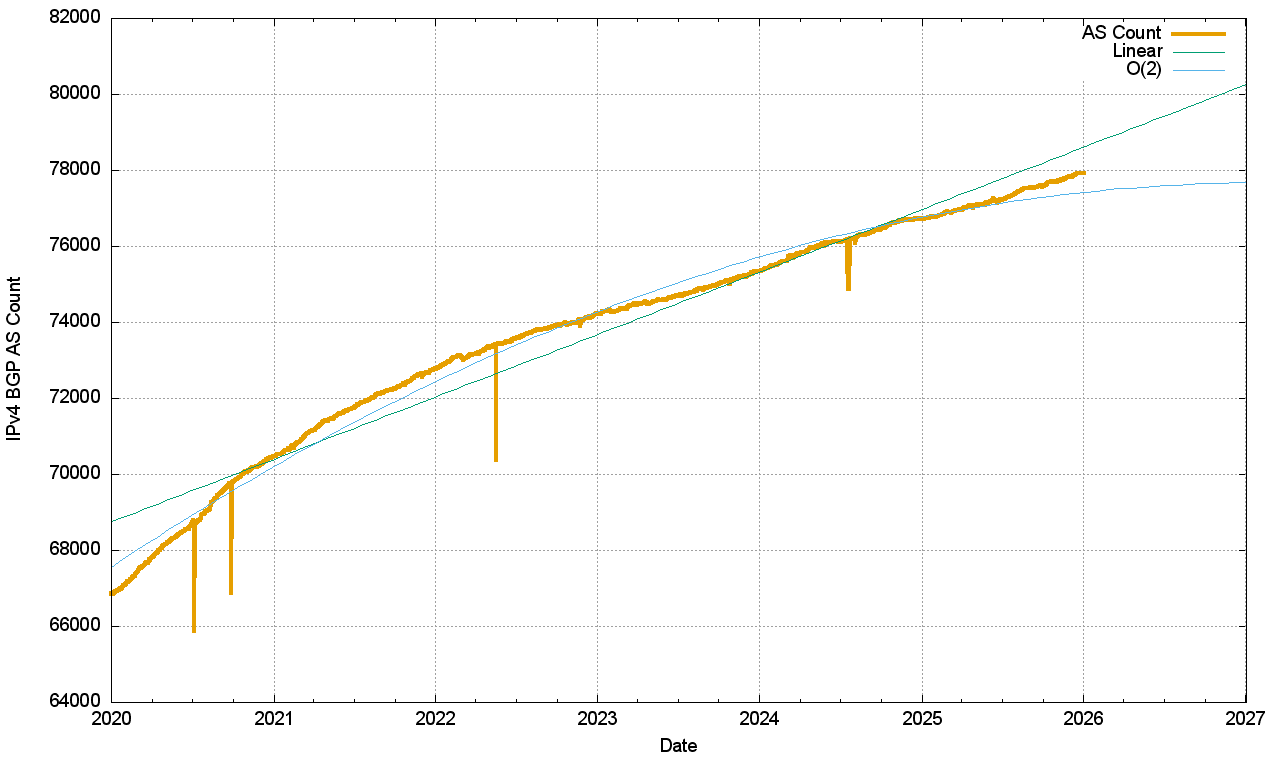

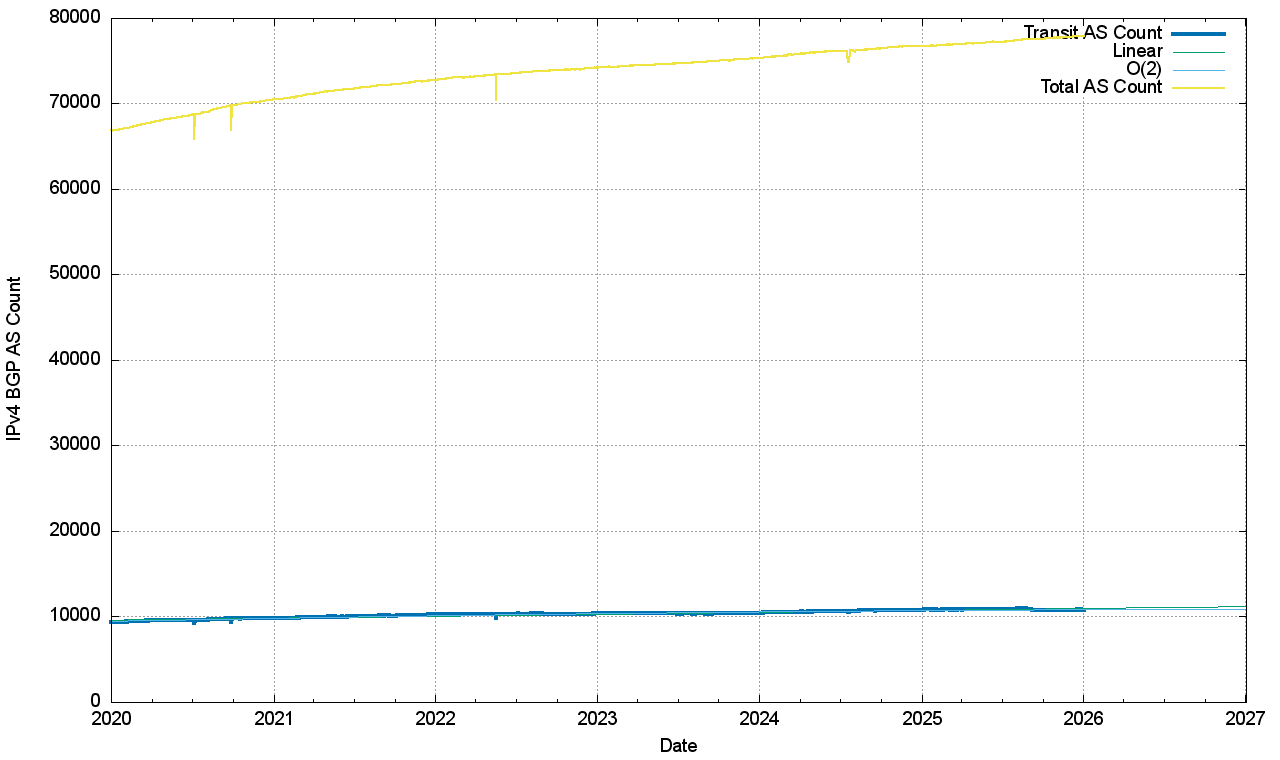

Evidence of the slowing of the growth in the IPv4 internet can be seen in the AS count (Figure 11). The growth of the AS count started to decline in late 2020 and has continued to decline in the ensuing years. This is a likely signal of network saturation in many markets. The number of transit networks was held constant across 2024, which appears to be a related signal of market saturation (Figure 12).

The year-by-year summary of the IPv4 BGP network (as seen by AS 131072) over the 2022-2026 period is shown in Table 1.

| Routing Table | Growth | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan-22 | Jan-23 | Jan-24 | Jan-25 | Jan-26 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||

| Prefix Count | 906,000 | 940,000 | 943,000 | 996,000 | 1,050,000 | 4% | 0% | 6% | 5% | ||

| Root Prefixes | 420,000 | 455,000 | 457,000 | 470,000 | 506,000 | 6% | 3% | 3% | 8% | ||

| More Specs | 486,000 | 495,000 | 486,000 | 526,000 | 544,000 | 2% | -2% | 8% | 3% | ||

| Address Span (B) | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0% | -1% | 2% | 0% | ||

| AS Count | 72,800 | 74,200 | 75,300 | 76,700 | 77,900 | 2% | 1% | 2% | 2% | ||

| Transit AS | 10,800 | 10,800 | 11,000 | 11,300 | 11,400 | 0% | 2% | 23 | 1% | ||

| Stub AS | 62,000 | 63,400 | 64,300 | 65,400 | 66,500 | 2% | 1% | 2% | 2% | ||

Table 1 – IPv4 BGP Table Growth Profile

In terms of advertised prefixes, the size of the routing table grew by some 54,000 entries, or 5%. The number of root prefixes increased by 36,000 entries, while the number of more specific routes increased by 18,000 entries.

The total span of advertised addresses decreased by some 11M IPv4 /32s across the year. Google, (AS15169) reduced its advertised span by 7.2M addresses, but this was more than offset by the span advertised by Google Cloud (AS396982) which increased by 156M addresses

The number of routed Stub AS numbers (edge networks) grew by 1.6% in 2024, and the total number of ASes visible in the IPv4 network grew by 351 ASes across 2024, or 3.2%.

Let’s look in a little more detail at the 10 networks that had the highest route object net growth, and the highest net route withdrawal count for the year (Table 2).

| V4 Advertised Prefix Growth | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS Num | Change | Jan-24 | Roots | More Specs. | Dec-24 | Roots | More Specs. | Name, CC | |||

| AS9808 | 3,283 | 10,099 | 214 | 9,885 | 13,382 | 261 | 13,121 | CHINA MOBILE, CN | |||

| AS17561 | 2,178 | 948 | 948 | 0 | 3,126 | 3,124 | 2 | LARUS, HK | |||

| AS56046 | 1,770 | 1,630 | 215 | 1,415 | 3,400 | 220 | 3,180 | CHINA MOBILE JIANGSU, CN | |||

| AS16509 | 1,559 | 12,473 | 4,952 | 7,521 | 14,032 | 8,044 | 5,988 | AMAZON-02, US | |||

| AS11404 | 1,437 | 168 | 128 | 40 | 1,605 | 781 | 824 | WAVE, US | |||

| AS398781 | 1,193 | 41 | 41 | 0 | 1,234 | 722 | 512 | OSL, US | |||

| AS22773 | 1,175 | 3,574 | 227 | 3,347 | 4,749 | 1,584 | 3,165 | COX, US | |||

| AS8151 | 1,132 | 11,563 | 2,212 | 9,351 | 12,695 | 2,231 | 10,464 | UNINET, MX | |||

| AS6079 | 1,112 | 602 | 589 | 13 | 1,714 | 1,688 | 26 | RCN, UX | |||

| AS7459 | 1,063 | 463 | 34 | 429 | 1,526 | 1,095 | 431 | GRAND ECOM, US | |||

| AS9304 | 977 | 507 | 69 | 438 | 1,484 | 1,029 | 455 | HUTCHISON, HK | |||

| AS56045 | 927 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 927 | 86 | 841 | CHINA MOBILE JIANGXI, CN | |||

| AS44559 | 887 | 267 | 267 | 0 | 1,154 | 1,154 | 0 | ITHOSTLINE, CY | |||

| AS834 | 852 | 516 | 516 | 0 | 1,368 | 1,368 | 0 | IPXO, US | |||

| AS7029 | 760 | 1,775 | 776 | 999 | 2,535 | 1,198 | 1,337 | WINDSTREAM, US | |||

| | V4 Advertised Prefix Reduction | ||||||||||

| AS Num | Change | Jan-24 | Roots | More Specs. | Dec-24 | Roots | More Specs. | Name, CC | |||

| AS7018 | -2,604 | 3,245 | 3,052 | 193 | 641 | 611 | 30 | AT&T, US | |||

| AS4155 | -2,268 | 2,291 | 2,291 | 0 | 23 | 21 | 2 | USDA, US | |||

| AS174 | -1,234 | 4,231 | 1,023 | 3,208 | 2997 | 1,123 | 1,874 | COGENT, US | |||

| AS28202 | -1,116 | 1,126 | 10 | 1,116 | 10 | 10 | 0 | MASTER, BR | |||

| AS984 | -945 | 1,280 | 613 | 667 | 335 | 252 | 83 | OWS, US | |||

| AS367 | -702 | 2,510 | 2,121 | 389 | 1,808 | 1,585 | 223 | DNIC, US | |||

| AS8100 | -647 | 670 | 360 | 310 | 23 | 22 | 1 | QUADRANET GLOBAL, US | |||

| AS6389 | -578 | 633 | 63 | 570 | 55 | 54 | 1 | BELLSOUTH, US | |||

| AS45271 | -510 | 905 | 741 | 164 | 395 | 342 | 53 | Vodafone Idea, IN | |||

| AS140224 | -473 | 498 | 496 | 2 | 25 | 25 | 0 | NEBULA, US | |||

| AS6503 | -444 | 1,167 | 193 | 974 | 723 | 448 | 275 | Axtel, MX | |||

| AS203999 | -428 | 521 | 521 | 0 | 93 | 93 | 0 | GEEKYWORKS, IN | |||

| AS12479 | -422 | 7,700 | 223 | 7,477 | 7,278 | 215 | 7,063 | UNI2, ES | |||

| AS29571 | -398 | 1,470 | 1,087 | 383 | 1,072 | 24 | 1,048 | ORANGE, COTE-IVOIRE, CI | |||

| AS15133 | -384 | 404 | 404 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 | EDGECAST, US | |||

Table 2 – IPv4 Advertised Prefix Changes – Top 15 ASes

The majority of additional route objects are more specifics. The highest growth in route objects over 2025 was AS9808 (China Mobile), where the number of more specifics grew by 3,283 routes, where number number of root prefixes increased by 47 prefixes, and the rest were more specifics.

We can also look at the total span of advertised addresses for each AS, comparing the advertised address space at the start of 2025 with that at the end of the year. This data is shown in Table 3.

| Net Growth (M addresses) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS Num | Change | Jan-25 | Dec-25 | Name, CC | ||

| AS396982 | 4.96 | 14.97 | 19.93 | GOOGLE-CLOUD, US | ||

| AS56 | 3.95 | 3.81 | 7.76 | DNIC, US | ||

| AS2856 | 3.59 | 12.26 | 15.85 | BT-UK, GB | ||

| AS6167 | 3.15 | 13.93 | 17.08 | CELLCO, US | ||

| AS16509 | 2.78 | 154.76 | 157.54 | AMAZON-02, US | ||

| AS8434 | 2.65 | 0 | 2.64 | TELENOR, SE | ||

| AS4155 | 2.47 | 668,928 | 3.14 | USDA, US | ||

| AS56045 | 1.96 | 0 | 1.96 | CHINA MOBILE JIANGXI, CN | ||

| AS6079 | 1.84 | 1.72 | 3.56 | RCN, US | ||

| AS9141 | 1.60 | 4,608 | 1.61 | P4 Play, PL | ||

| AS31898 | 1.37 | 3.30 | 4.68 | ORACLE, US | ||

| AS13285 | 1.35 | 2.92 | 4.28 | OPAL TELECOM, GB | ||

| AS14618 | 1.24 | 18.20 | 19.44 | AMAZON-AES, US | ||

| AS11404 | 1.22 | 763,136 | 1.98 | WAVE, US | ||

| AS25019 | 1.14 | 4.31 | 5.46 | SAUDINET, SA | ||

| | ||||||

| Net Reduction (M addresses) | ||||||

| AS Num | Change | Jan-25 | Dec-25 | Name, CC | ||

| AS15169 | -7.26 | 9.15 | 1.88 | GOOGLE, US | ||

| AS367 | -4.61 | 12.33 | 7.72 | DNIC, US | ||

| AS7738 | -3.53 | 7.40 | 3.86 | V tal, BR | ||

| AS7018 | -3.49 | 96.31 | 92.81 | AT&T, US | ||

| AS37963 | -2.81 | 12.05 | 9.23 | ALIBABA, CN | ||

| AS17676 | -2.76 | 40.43 | 37.66 | SoftBank, JP | ||

| AS2119 | -2.64 | 6.89 | 4.24 | TELENOR, NO | ||

| AS7922 | -2.08 | 70.11 | 68.02 | COMCAST, US | ||

| AS6830 | -1.63 | 2.76 | 1.12 | LIBERTY GLOBAL, NL | ||

| AS6389 | -1.31 | 5.89 | 4.58 | BELLSOUTH, US | ||

| AS37518 | -1.11 | 1.11 | 768 | FIBERGRID, SC | ||

| AS12322 | -1.04 | 10.98 | 9.93 | PROXAD, FR | ||

| AS984 | -1.03 | 1.20 | 172,288 | OWS, US | ||

| AS721 | -1.00 | 73.09 | 72.10 | DNIC, US | ||

| AS3356 | -0.90 | 29.77 | 28.88 | LEVEL3, US | ||

Table 3 – IPv4 Advertised Address span – Top 10 ASes

The picture of IPv4 growth for the year 2025 was dominated by Google Cloud (AS396982), which expanded from by 56M addresses, increasing from 5M addresses to 15M addresses through 2025. This was likely to be due to an internal reshuffling of networks within Google, with AS15169, another Google network, reducing its advertised address span by 7M addresses The next largest was the US military network AS 56 which expanded by 4M addresses, but this was also due to an internal re-organisation of their network, moving advertisements from AS367 to AS56.

It’s likely that we are seeing a number of factors at play behind these changes in the IPv4 network:

- The first major factor appears to be the saturation of many Internet markets across the globe, so that the amount of “green field” expansion of the Internet into new market segments is far lower than, say, a decade ago.

- Secondly, we are seeing considerable concentration on the service market, where the provision of content and services is undertaken using fewer, but far larger, service platform operators. The service and client numbers may be growing, but that does not necessarily imply the use of more IPv4 addresses or more routing table entries. NATs are fully entrenched in the IPv4 world, and in the service provider market volume economics implies that few larger providers are more efficient than a greater number of smaller providers in terms of their address demands for service use.

- Thirdly, this concentration in the service market has been accompanied by further consolidation in the access market, particularly in mobile access networks. This consolidation of client access networks creates greater efficiencies in shared address solutions.

- The continued deployment of IPv6 cannot be ignored. Within the 10 economies with the largest span of advertised addresses (collectively, these 10 economies advertise 75% of the span of advertised IPv4 addresses) 7 of these economies are also in the 10 economies with the largest span of advertised IPv6 addresses (collectively, these same 10 economies advertise 76.5% of the span of advertised IPv6 addresses). Looking at just these 7 economies, namely the United States, China, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Canada, they advertise 76.3% of the entire advertised IPv6 address span and 67.5% of the advertised IPv4 address span.

- I suspect that the most significant factor for the public Internet has been the inexorable rise of private content distribution and service delivery networks (CDNs and cloud infrastructure). The conventional drivers for growth in the routing table were based on the product of an increasing number of networks with discrete routing policies and the need for these networks to balance incoming service and content transit traffic across multiple network paths (or "traffic engineering using more specifics in BGP"). The rapid uptake of CDNs by service platforms has meant a significantly reduced level of dependence on BGP transit services to deliver content to users. The public part of the Internet is rapidly shrinking to the last mile access network, which connects directly to a number of CDNs. The transit part of the Internet is just not so critical for service delivery to end users these days. It is likely that we will continue to move further down the path leading to ubiquitous use of CDNs in the foreseeable future, and if anything, their level of use within the Internet’s service portfolio will increase further.

- However, the Internet reaches well beyond the mode of the provision of services and content on the public Internet. The enterprise cloud market continues to influence IP address demands, and IPv4 addresses in particular. The providers of cloud-based services to enterprises, notably Amazon, Microsoft and Google, have been very active in expanding their offerings to service an industry-wide transition from in-house computing services to cloud-based service solutions for enterprises. This sector of the market appears to operate in a quite conservative mode, so there is a continued preference for IPv4-based cloud services, and a continued pressure for cloud operators to meet this demand with extensive IPv4 cloud platform infrastructure. Over 2025 we saw the expansion of the advertised address span announced by bdoth Google and Amazon cloud service platforms.

In various parts of the network the number of IPv4 entries in the default-free zone is between 1,040,000 and 1,050,000 entries. The net IPv4 routing table growth in 2025 was some 44,000 new entries, a slight decrease over the 52,000 new entries seen in 2024. A net increase of 1,250 new AS numbers were seen in the IPv4 network across the year, compared to 1,400 in 2023. While 2023 saw a slowing of the IPv4 network growth, 2024 and 2025 both saw a growth in these numbers to the levels previously seen in 2021 and 2022. That said, these are not high growth numbers in any sense. They are on the order of 2% or so, which appears to be aligned to natural population growth, as distinct from the form of growth that results from the opening up of new Internet markets.

The IPv6 BGP Table Data

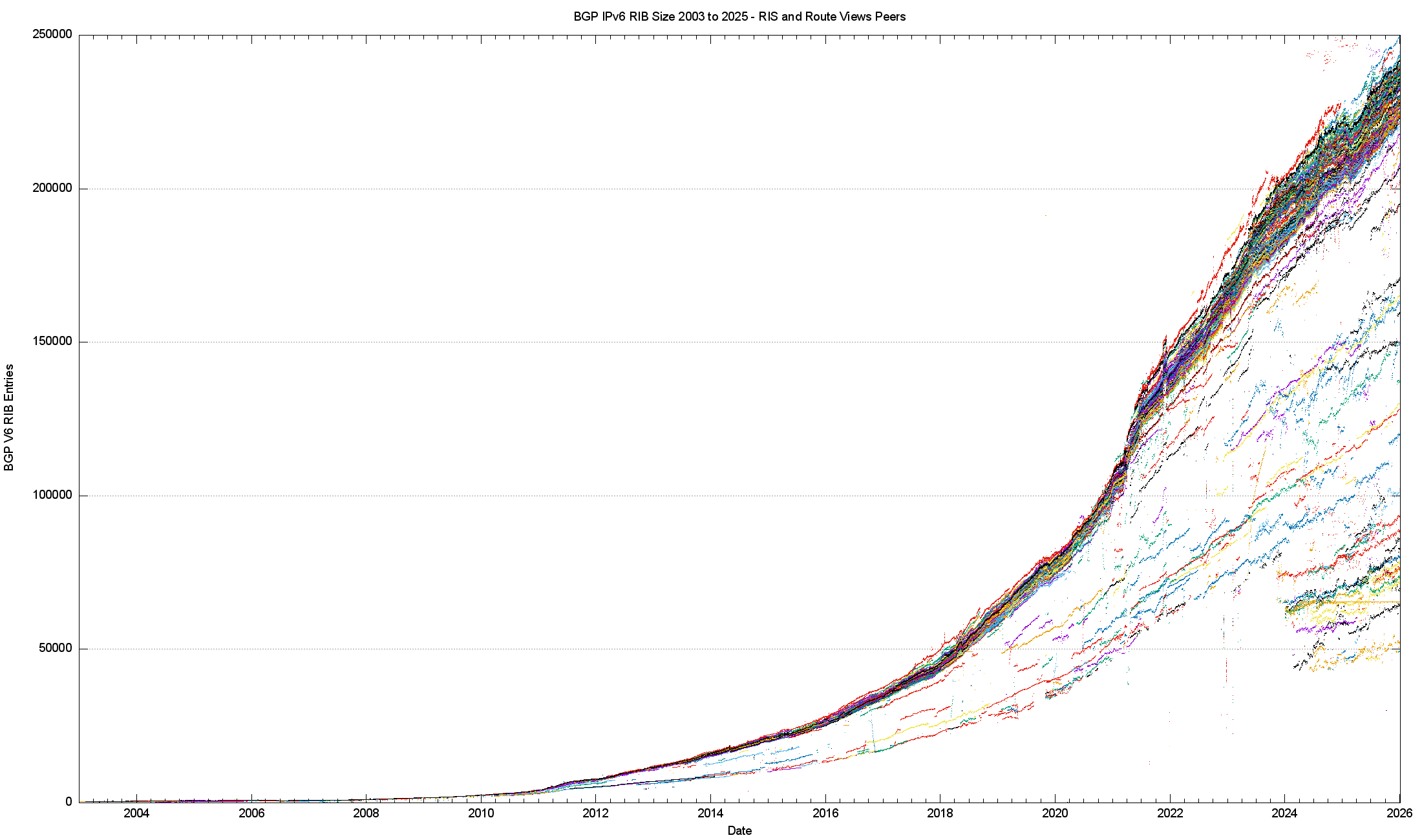

A similar exercise has been undertaken for IPv6 routing data. As with the IPv4 network, there is diversity in the number of IPv6 routes seen at various vantage points, as shown when looking at the total prefix count in advertised prefixes by all the peers of RouteViews and RIS (Figure 14).

Figure 14 – IPv6 routing table since 2004 as seen by RIS and RouteViews peers

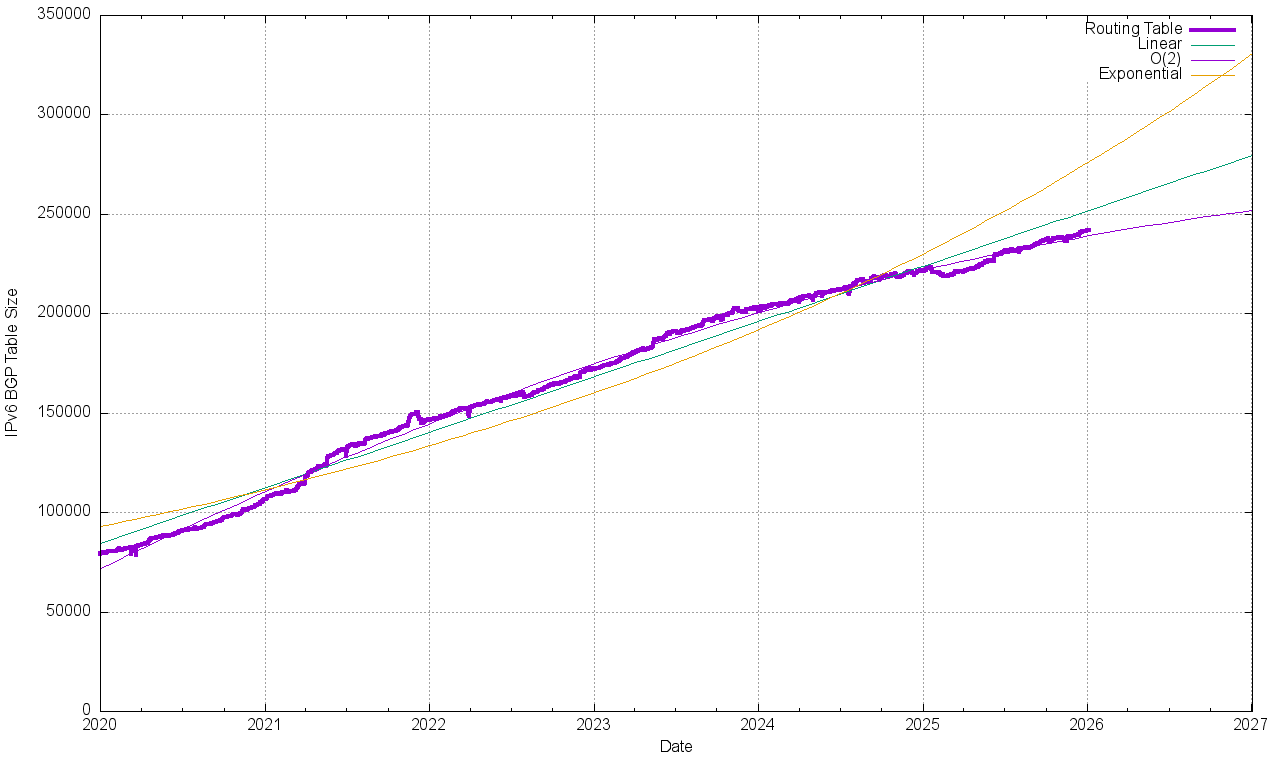

There are two distinct phases in the growth trends that are visible in this history of the IPv6 routing table. The period between 2004 and late 2021 could be modelled by an exponential growth function with a doubling interval of approximately three years. The second phase is four years of linear growth from 2022 to the end of 2025, where the IPv6 routing table is growing by some 27,000 additional prefixes per year.

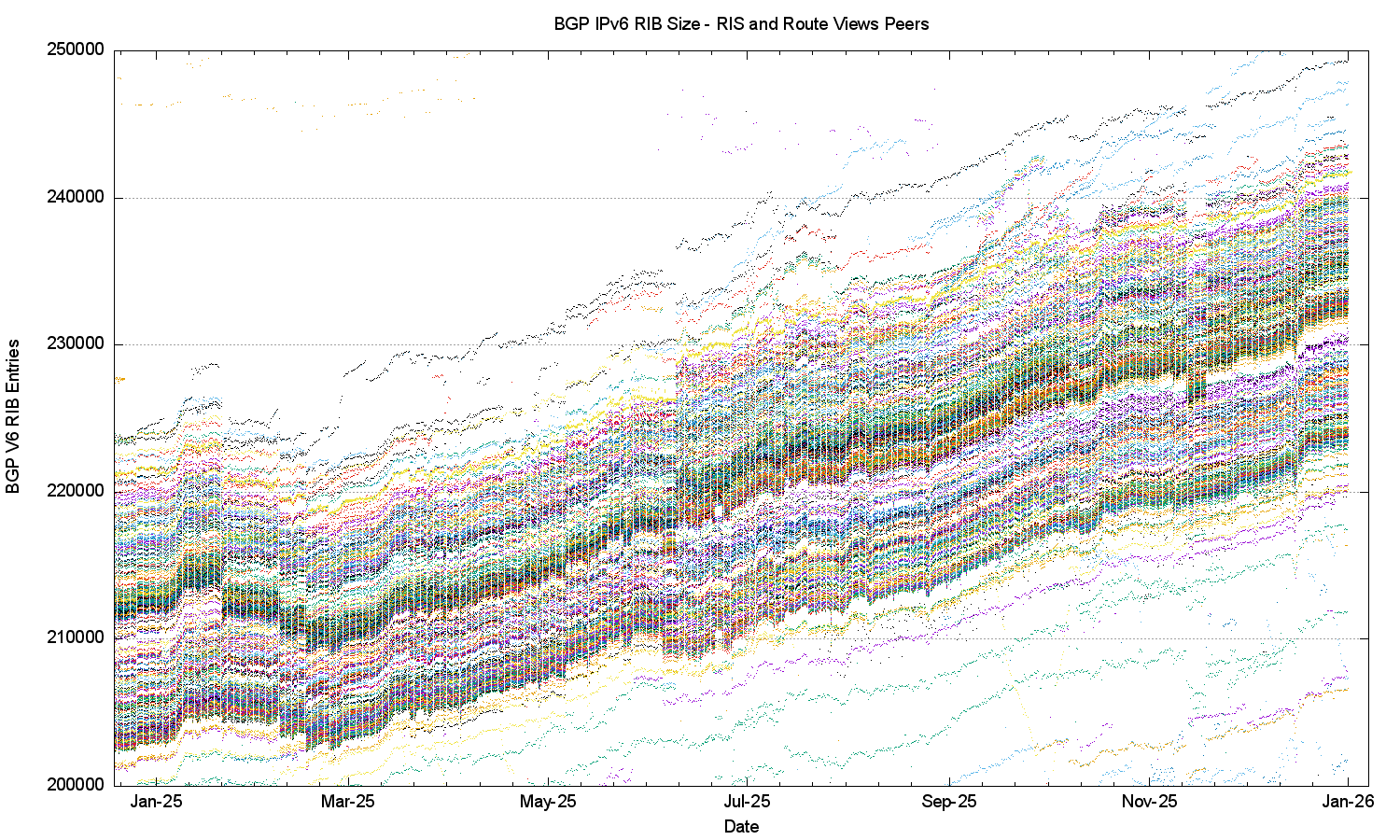

A more detailed look at 2025, incorporating both RouteViews and RIS data (Figure 15) shows the diversity between various BGP views as to what constitutes the “complete” IPv6 route set, and the variance at the end of 2025 now spans some 20,000 prefix advertisements.

Figure 15 – IPv6 routing table 2025 as seen by RouteViews and RIS peers

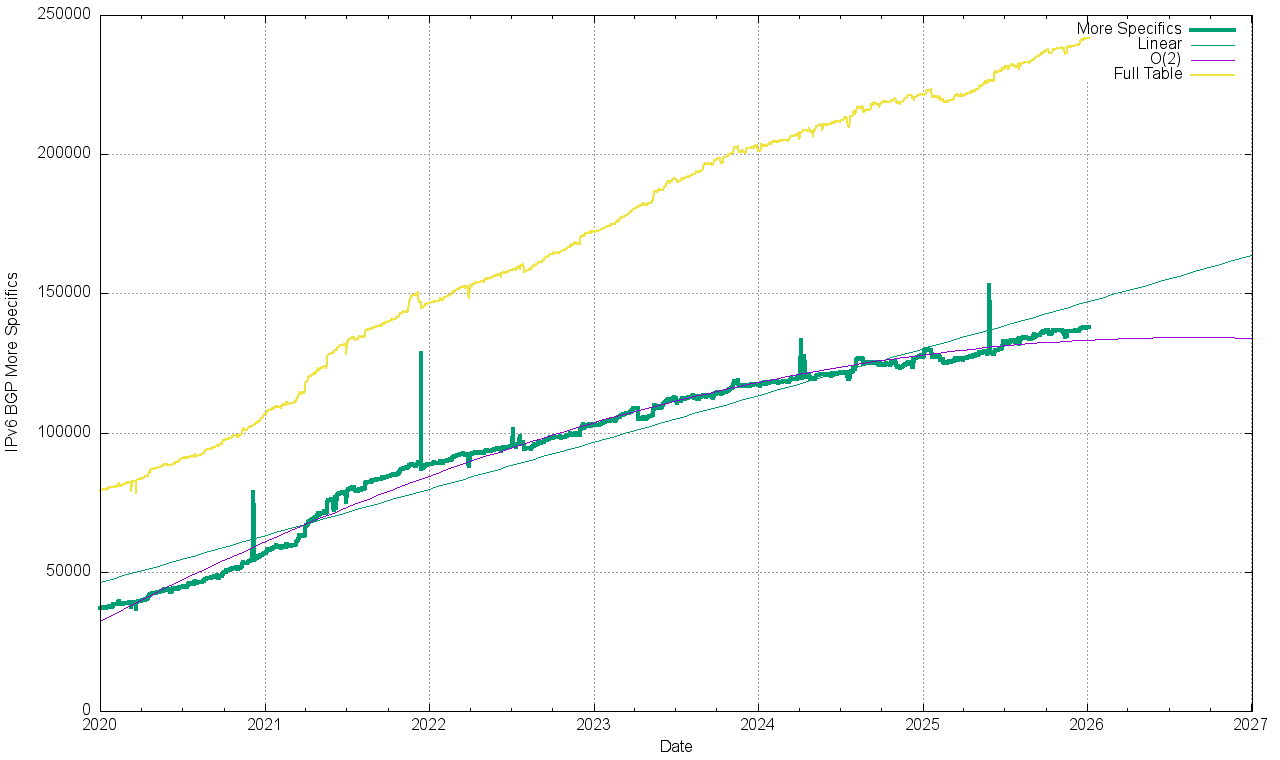

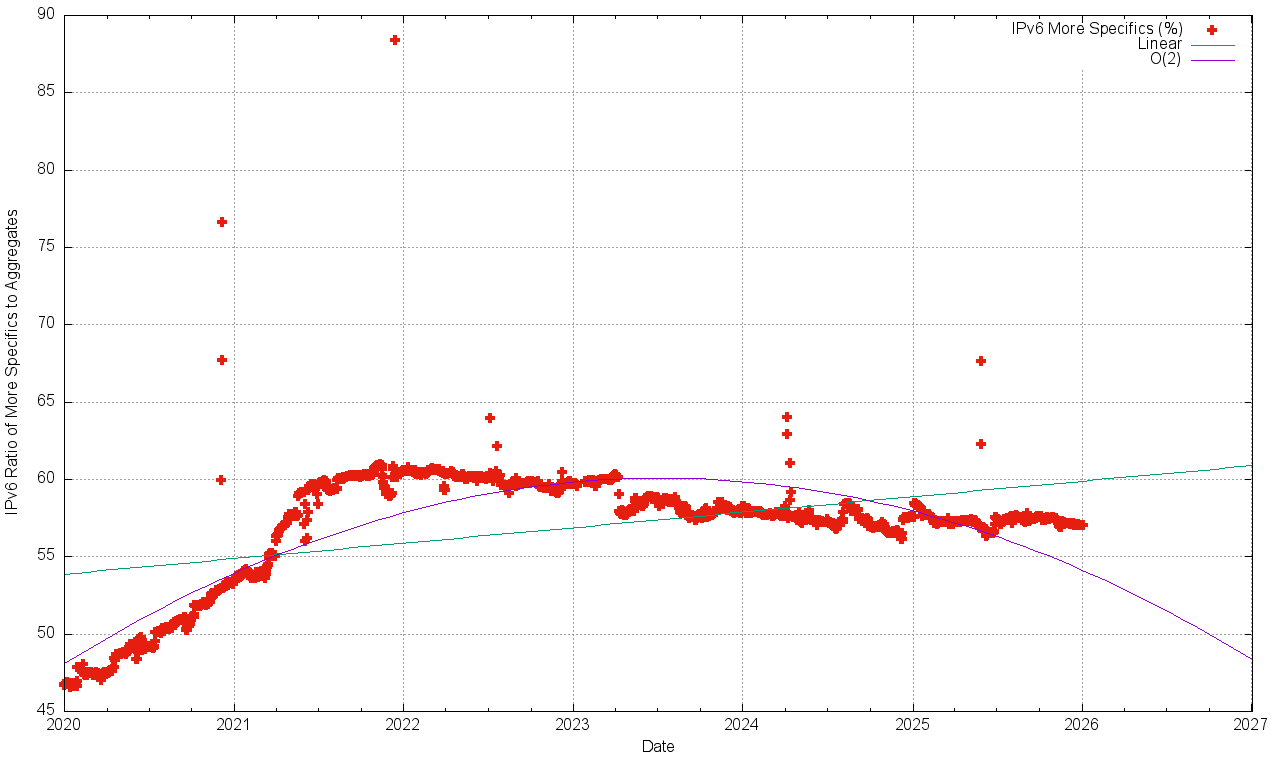

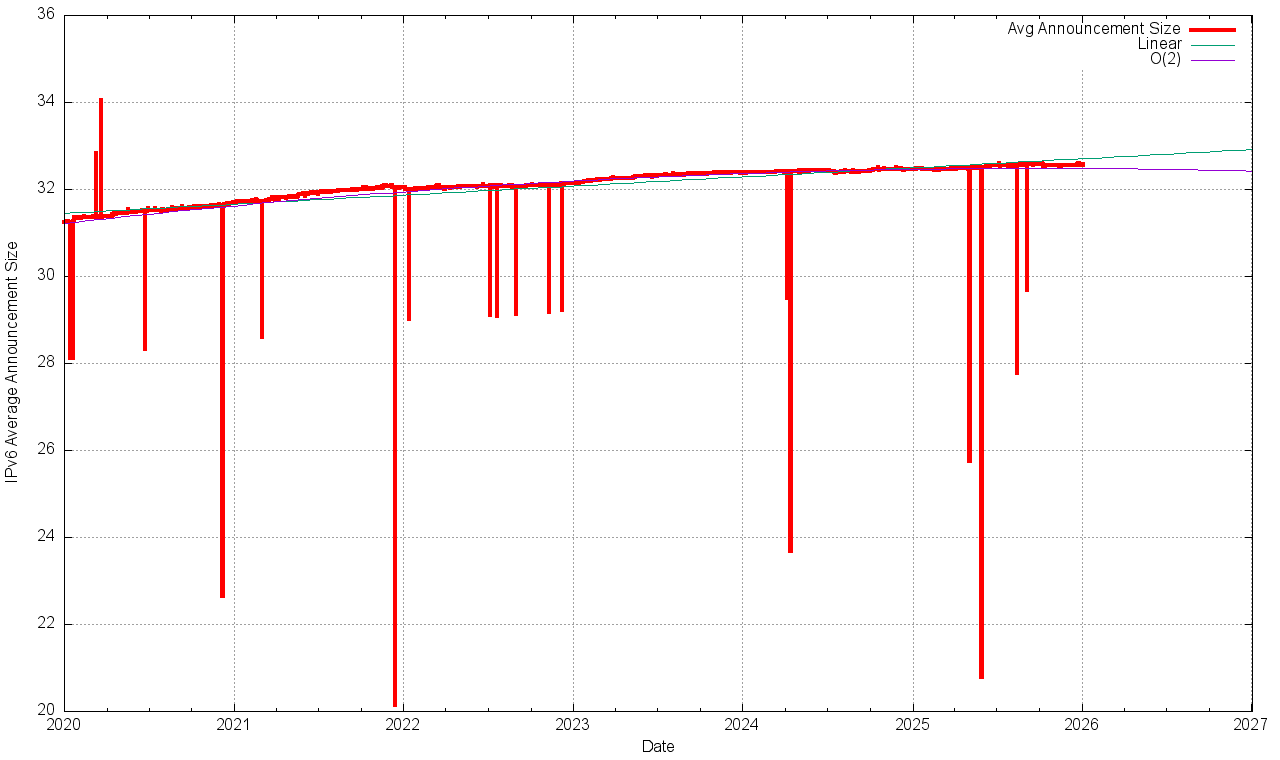

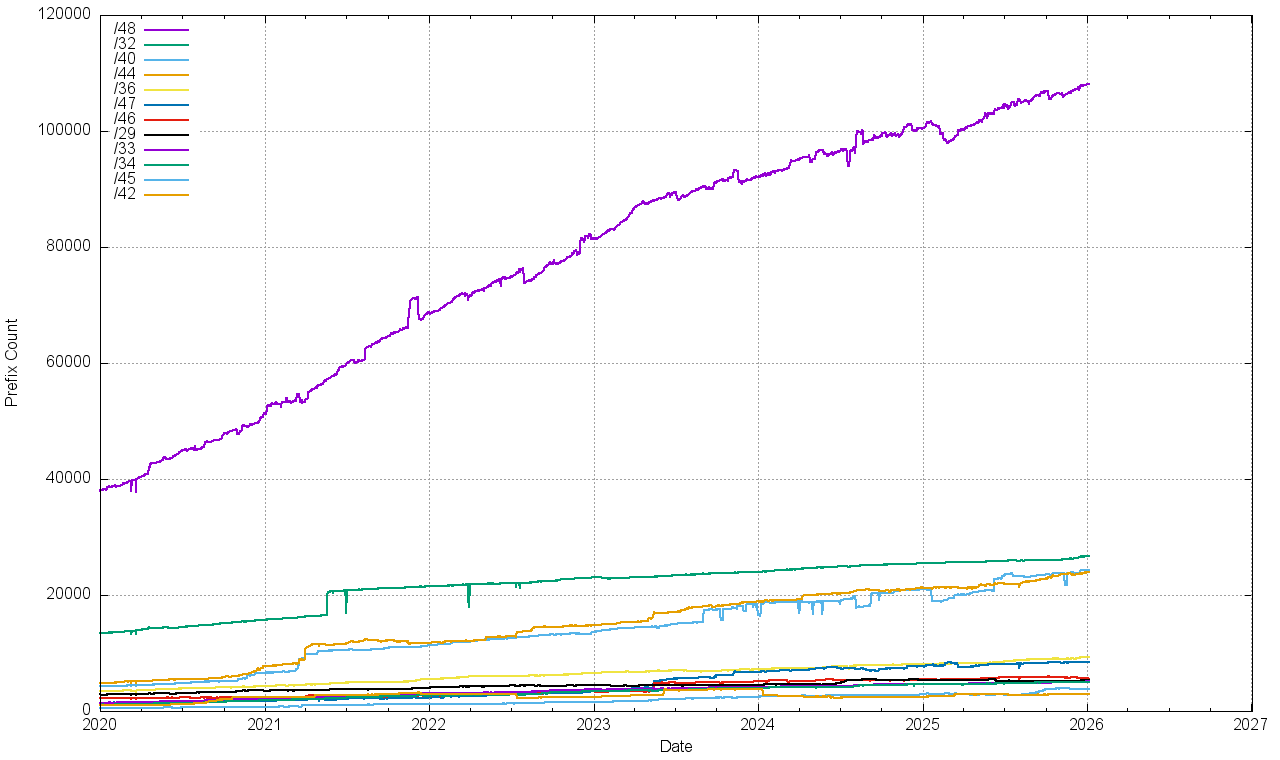

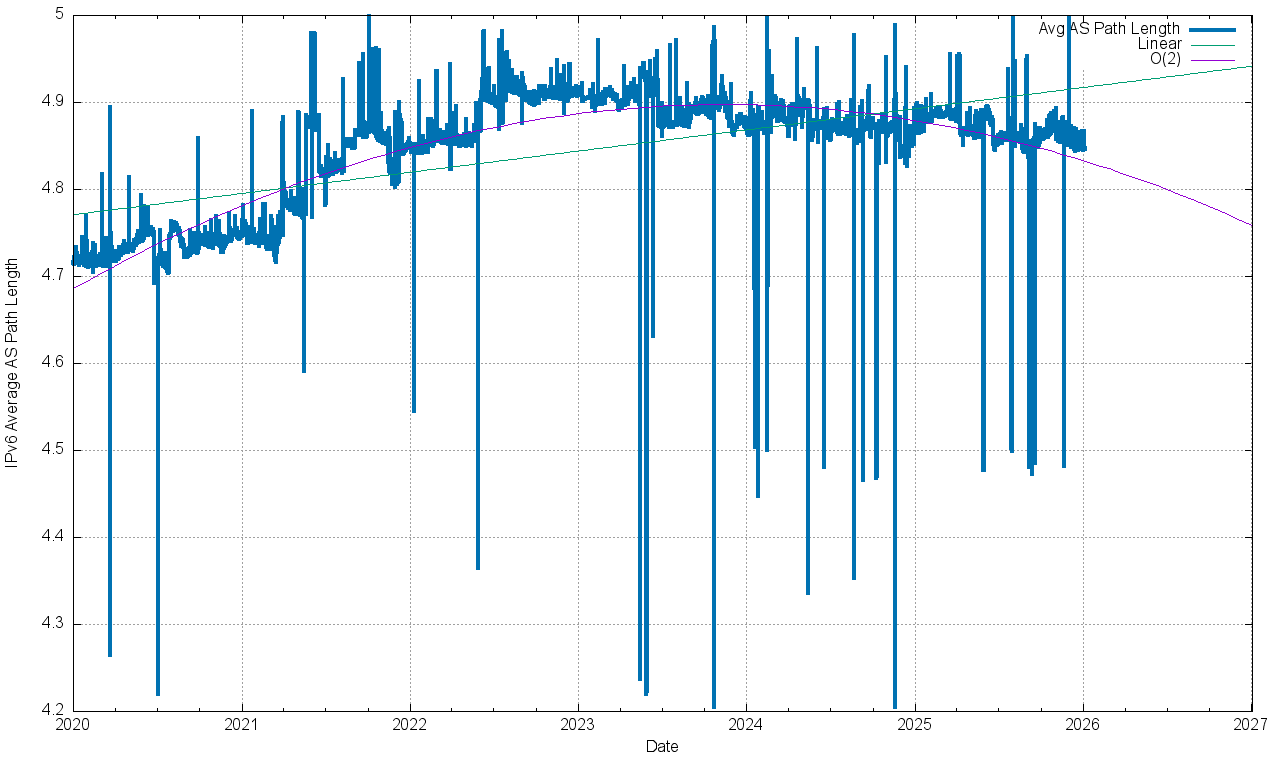

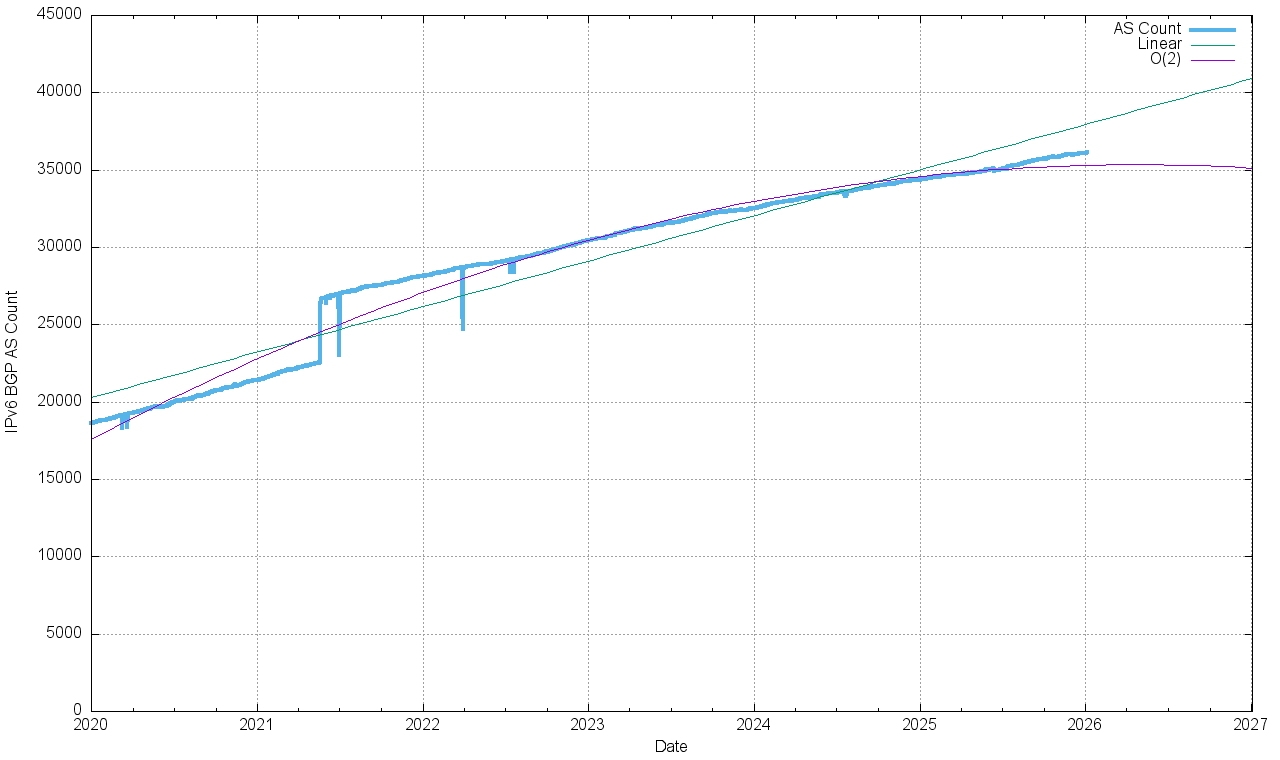

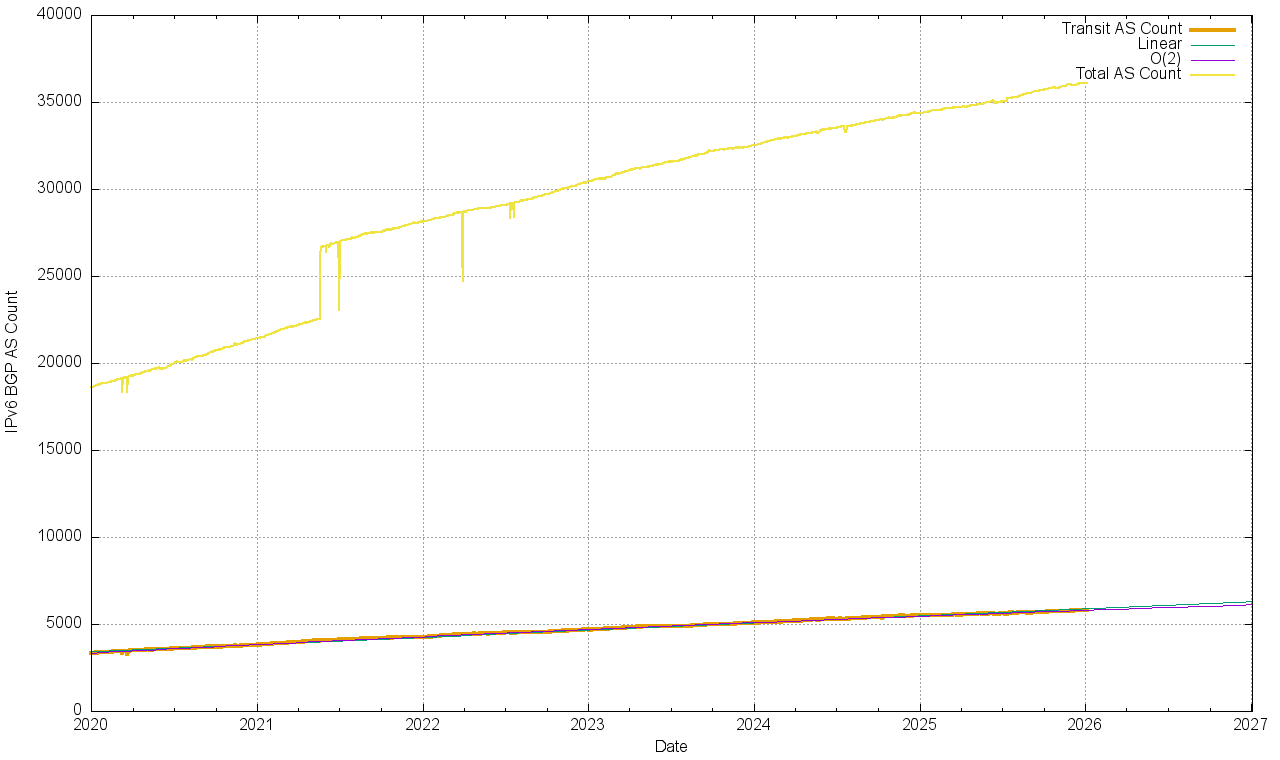

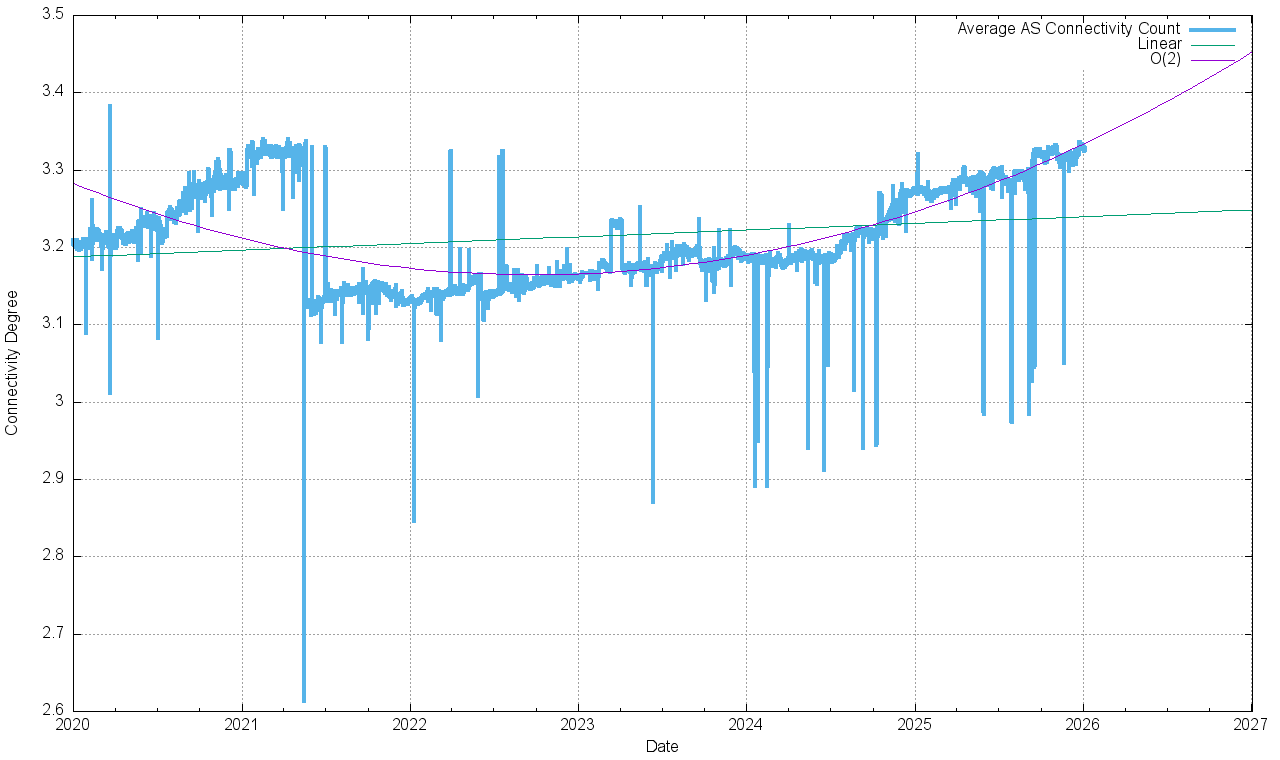

The comparable profile figures for the IPv6 Internet are shown in Figures 16 through 25.

| ||

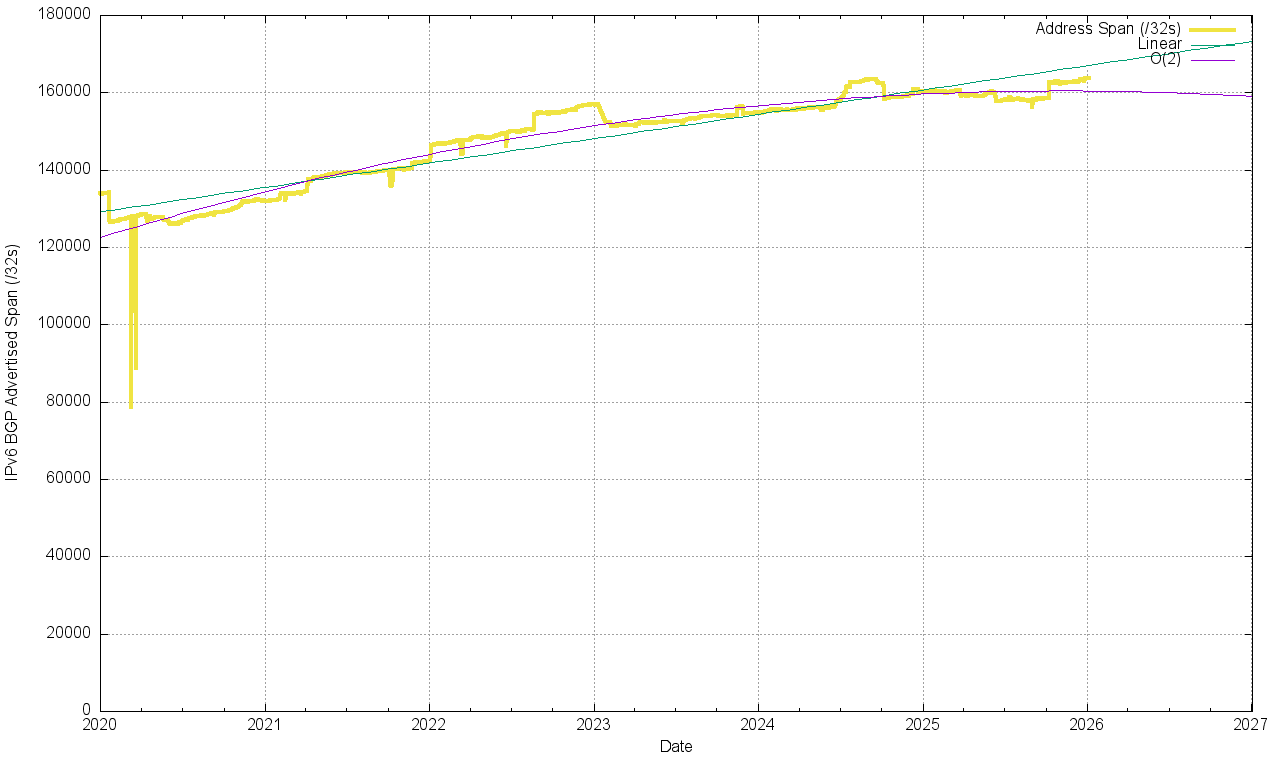

The IPv6 routing table reduced in size by some 3,000 entries across the first two months of 2025, then grew by a steady 2,000 additional table entries per month for the remainder of the year. (Figure 16). The span of advertised addresses remained constant for most of the year, with the addition of an advertised /20 in October by Cable One (AS 11492). More specific address prefixes rose by 10,000 across the year, as did the number of root prefixes (Figure 18), so the ratio of more specifics to the total number of advertised prefixes remained relatively constrant (Figure 19). The average prefix size remained relatively constant through the year, slightly larger than a /33 (Figure 20). Routing advertisements of /48s are by far the most prevalent prefix size in the IPv6 routing table, and some 45% of all prefixes are /48’s. A total of 76% of the IPv6 table entries are composed of /48, /32, /44, and /40 prefixes (Figure 21).

RIR allocations of IPv6 addresses show a different pattern, with 74% of the 68,879 IPv6 address allocations recorded in the RIRs’ registries are either a /32 (47%) or a /29 (24%). Only 21% of allocations are a /48.

What is evident is that there is no clear correlation between an IPv6 address allocation prefix size (as used by the address registries in the address allocation process) and the advertised address prefix size. Many IPv6 address holders do not advertise their entire allocated IPv6 address prefix in a single routing advertisement.Why is the IPv6 routing table being fragmented so extensively? The conventional response is that this is due to the use of more specific route entries to perform traffic engineering. Another possible reason is the use of more specifics to counter efforts of route hijacking. This latter rationale also has some credibility issues, given that it appears that most networks appear to accept a /64 prefix, and the disaggregated prefix is typically a /48, so as a countermeasure for more specific route hijacks, advertising /48’s may not be all that effective.

This brings up the related topic of the minimum accepted route object size. The common convention in IPv4 is that a /24 prefix advertisement is the smallest address block will propagate across the entire IPv4 default-free zone. More complex minimum size rules have largely fallen into disuse as address trading appears to have sliced up many of the larger address blocks into smaller sizes. If a /24 is the minimum accepted route prefix size in IPv4, what is the comparable size in IPv6? There appears to be no common consensus position here, and the default action many network operators appears have no minimum size filter at all. In theory, that would imply that a /128 route object would be accepted across the entire IPv6 default-free zone, but a more pragmatic observation is that a /32 would be assuredly accepted by all networks, and it appears that many network operators believe that a /48 is also generally accepted. Given that a /48 is the most common prefix size in today’s IPv6 network this view appears to be widespread. However, we also see prefixes smaller in size than a /48 in the routing table with /49, /52, /56 and /64 prefixes present in the IPv6 BGP routing table. Some 0.7% all advertised prefixes are more specific than a /48.

The summary of the IPv6 BGP routing table profile for period 2022 through to the start of 2026 is shown in Table 4. The IPv6 network growth rate in somewhat lower than previous years, with a 9% growth in routing entries, and a 2% growth in the advertised address span. All routing table metrics for IPv6 show a progressively lower growth rate over the most recent four years.

| Routing Table | Growth | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan-22 | Jan-23 | Jan-24 | Jan-25 | Jan-26 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

| Prefix Count | 146,500 | 172,400 | 201,200 | 221,500 | 241,800 | 18% | 17% | 10% | 9% | ||

| Root Prefixes | 57,800 | 69,400 | 84,000 | 94,000 | 103,900 | 20% | 21% | 12% | 11% | ||

| More Specifics | 88,700 | 103,000 | 117,200 | 127,500 | 137,900 | 16% | 14% | 9% | 8% | ||

| Address Span (/32s) | 142,300 | 157,000 | 155,000 | 161,000 | 164,000 | 10% | -1% | 4% | 2% | ||

| AS Count | 28,140 | 30,439 | 32,500 | 34,360 | 36,100 | 8% | 7% | 6% | 5% | ||

| Transit AS Count | 4,640 | 4,990 | 5,400 | 5,800 | 6,200 | 8% | 8% | 7% | <7% | /tr>||

| Stub AS Count | 23,500 | 25,440 | 27,100 | 28,560 | 29,900 | 8% | 7% | 5% | 5% | ||

Table 4 – IPv6 BGP Table Growth Profile

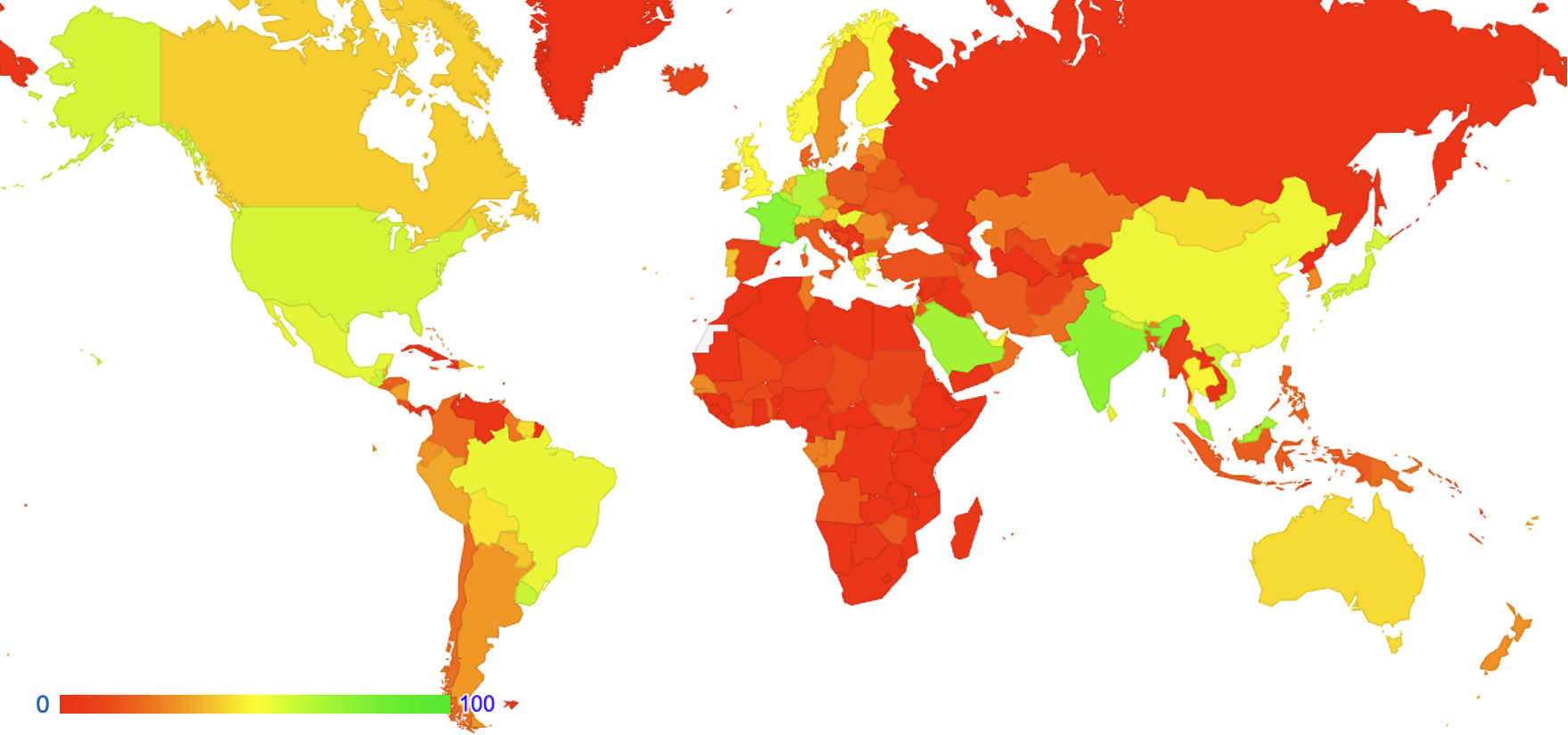

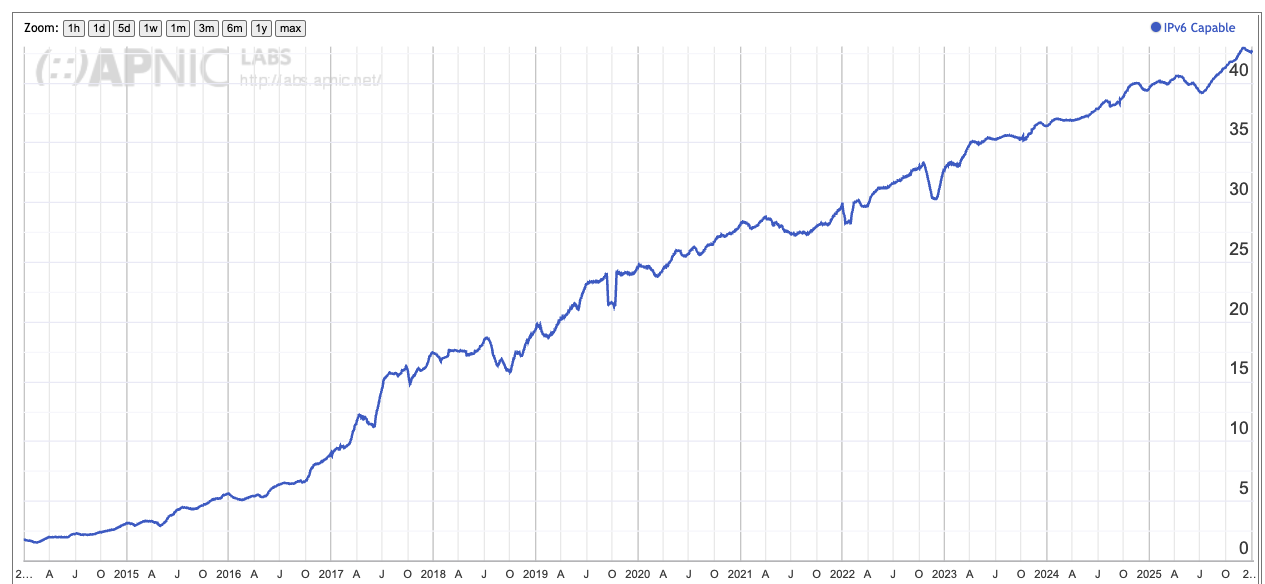

The pressures for further expansion on the IPv6 network appear to be more idiosyncratic for each market sector and region, rather than being expressed as a more general imperative. The only major market where there is visible movement in the adoption of IPv6 at present is China, where the proportion of IPv6-capable users continues to grow at some 10% per year. Where there is at present scant IPv6 adoption, as is the case in most of Africa, the Middle East, Eastern and Southern Europe, and the western part of Latin America (Figure 26), there is no apparent sense of urgency to make the shift. It would appear that the Internet market is largely a saturated one and the smaller pace of network growth in those regions appears, for the moment, be adequately accommodated in the continued use of IPv4 NATs.

Figure 26 – IPv6 Adoption asas of December 2024 (https://stats.labs.apnic/net/ipv6)

The Predictions

What can this data tell us in terms of projections of the future of BGP in terms of BGP table size?

Forecasting the IPv4 BGP Table

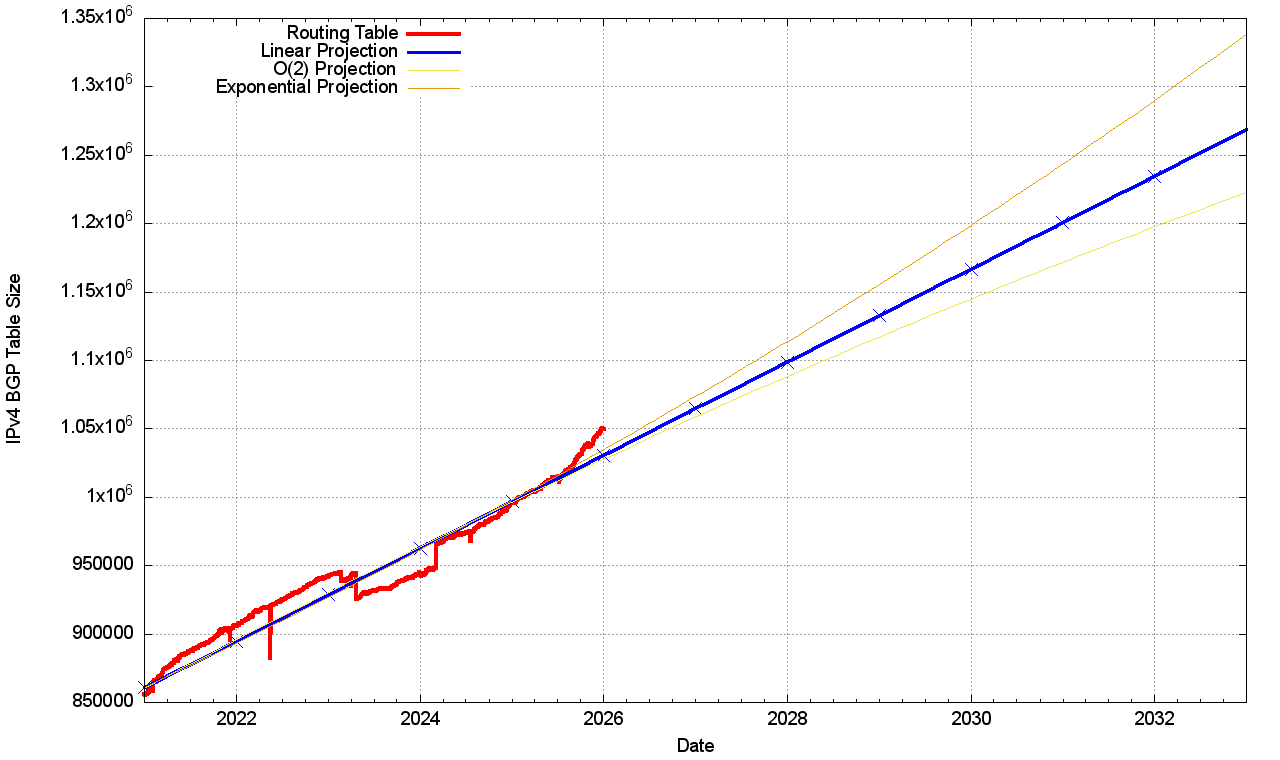

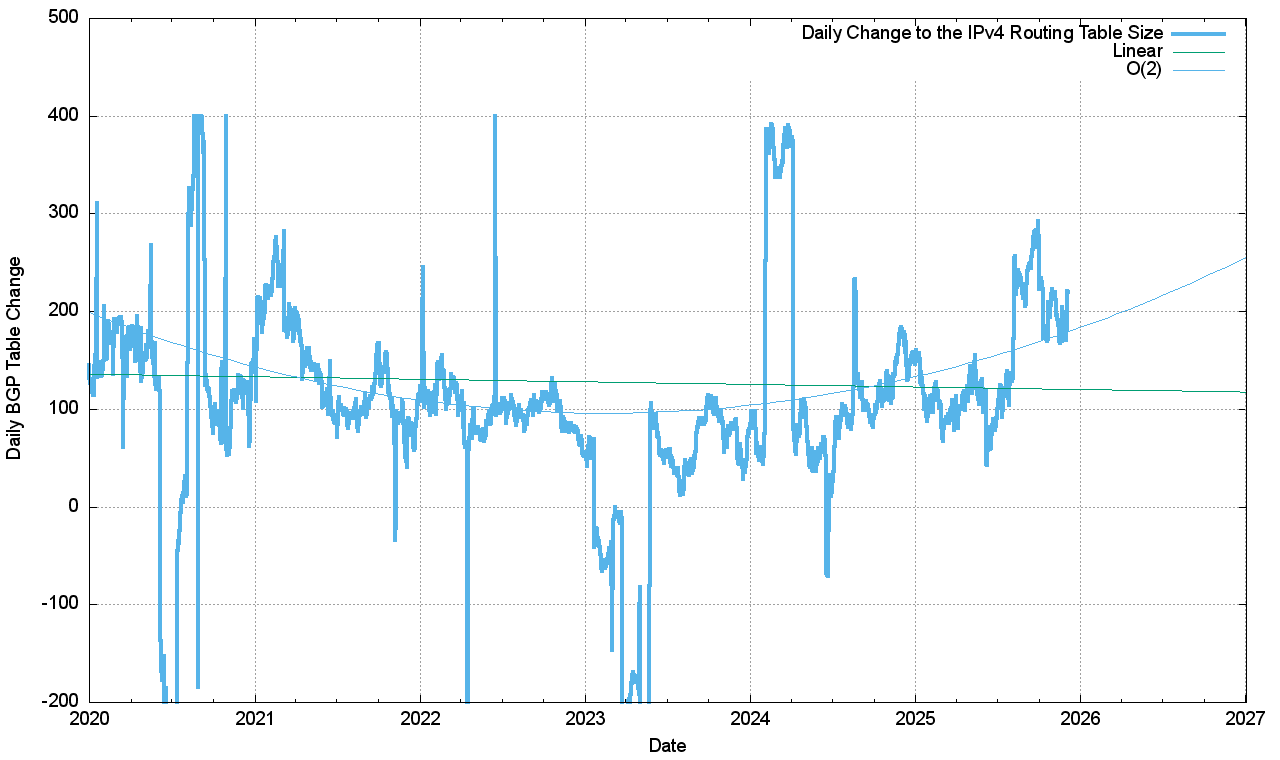

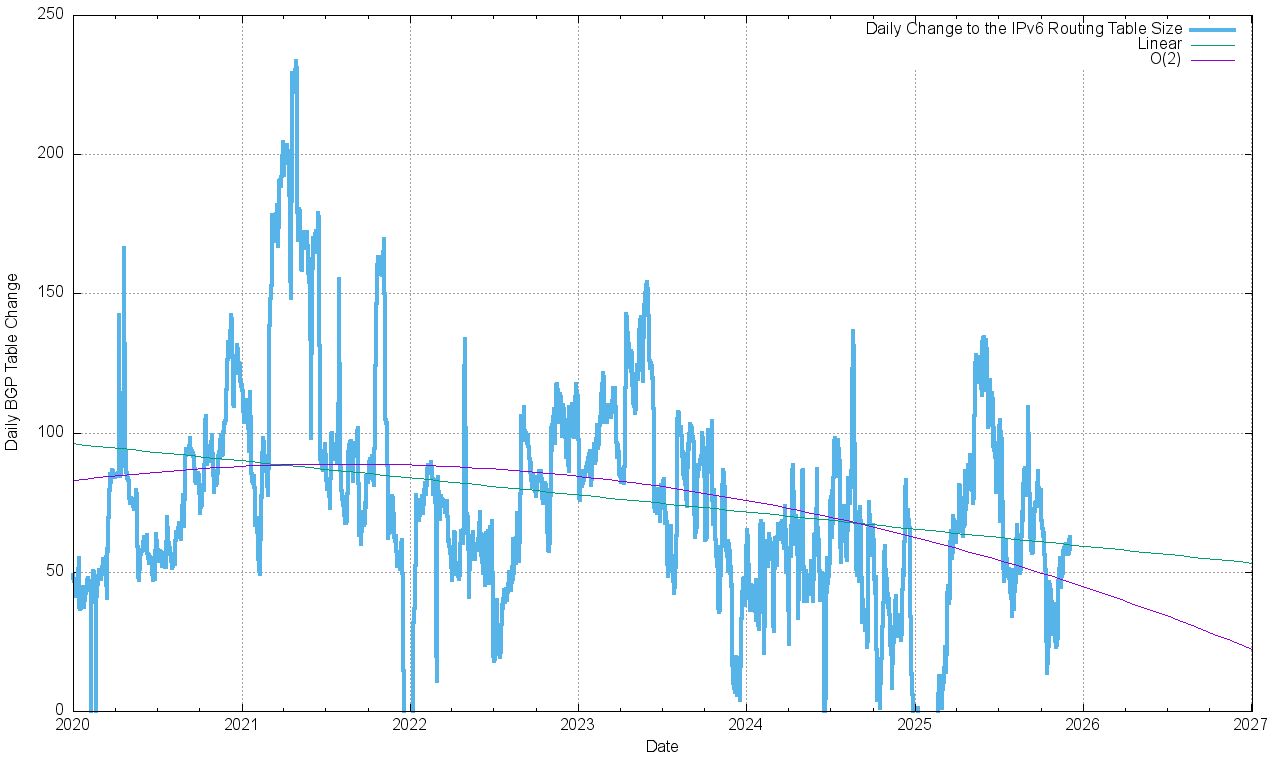

Figure 27 shows the data set for BGP from January 2017 until January 2026. This plot also shows the fit of these most recent 5 years of data to various growth models. The first-order differential, or the rate of growth, of the BGP routing table is shown in Figure 28. The linear average rate of growth of the routing table appears be falling slowly from 140 to 160 additional entries per day in 2016 to around 100 per day at the start of 2024.

There are a number of potential models to match this data. One model is to take the five-year average daily rate of change and apply this as a continuous model for the next five years. This is a “linear” model and takes the current dynamics of the IPv4 Internet, making the assumption that these dynamics will operate largely unchanged over the projection period. The second model is to look at the trend in the changes of rate of change and match this to a linear model (the first order differential). If this first order differential of a data series is a linear function, then the original data can be represented as a second order polynomial (x2). The final model used here is to model the log of the data series as a linear model and therefore derive an exponential model for the data series (ex). The application of these three projection models to the original data series is shown in Figure 27, and the first order differential of the data (the daily rate of change) is shown in Figure 28.

Figure 27 – IPv4 BGP Table 2016 – 2026 with forward projections

Figure 28 -First Order Differential of Smoothed IPv4 BGP Table Size – 2016 - 2026

The first order differential data shows a daily change of 100 additional prefixes per day between mid-2021 and mid 2025, while the last half of 2025 saw the growth rate double to some 200 per day. It appears that the best fit to the recent BGP data is a linear fit, through the prospect of a longer term growth potential in what appears to be the end days of the IPv4 network seems to be somewhat far-fetched!

The projections of the linear and polynomial best fit models are shown in Table 4 (the resumption of an exponential growth model appears to be highly unlikely in this late phase of the IPv4 network).

| IPv4 Table | Projection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | O(2) Poly | ||

| Jan 2020 | 814,000 | ||

| Jan 2021 | 866,000 | ||

| Jan 2022 | 906,000 | ||

| Jan 2023 | 942,000 | ||

| Jan 2024 | 944,000 | ||

| Jan 2025 | 996,000 | ||

| Jan-2026 | 1,050,000 | 1,030,755 | 1,027,918 |

| Jan-2027 | 1,064,734 | 1,058,581 | |

| Jan-2028 | 1,098,712 | 1,088,297 | |

| Jan-2029 | 1,132,784 | 1,117,143 | |

| Jan-2030 | 1,166,763 | 1,144,962 | |

| Jan-2031 | 1,200,742 | 1,171,834 | |

| Jan 2032 | 1,234,721 | 1,197,758 | |

Table 5 – IPv4 BGP Table Size Prediction

Both projection models appear to me to be somewhat unlikely, in my opinion. The drivers for continued growth of the IPv4 network do not appear to be clearly evident, so the projection of continued growth of the number of IPv4 FIB entries with an annual net gain of 34,000 entries is somewhat unrealistic. The O(2) polynomial projection model predicts that this first order differential will reach the zero point by early 2058 and then decline. It must be stressed it’s just a mathematical model that fits the recent data, and nothing more.

Given that that last “normal” year of supply of available IPv4 address to fuel continued growth in the IPv4 Internet was now some fifteen years ago in 2010, perhaps the more relevant question is: Why has the growth of the IPv4 routing table persisted in the ensuring fifteen years?

It should be remembered that a dual-stack Internet is not the objective in this time of transitioning the Internet to IPv6. The ultimate objective of the entire transition process is to support an IPv6-only network. An important part of the process is the protocol negotiation strategy used by dual-stack applications, where IPv6 is the preferred protocol wherever reasonably possible. In a world of ubiquitous dual-stack deployment all applications will prefer to use IPv6, and the expectation is that in such a world the use of IPv4 would rapidly plummet.

The challenge for the past decade or more has been in attempting to predict when in time that tipping point that causes demand for IPv4 to plummet may occur.

Forecasting the IPv6 BGP Table

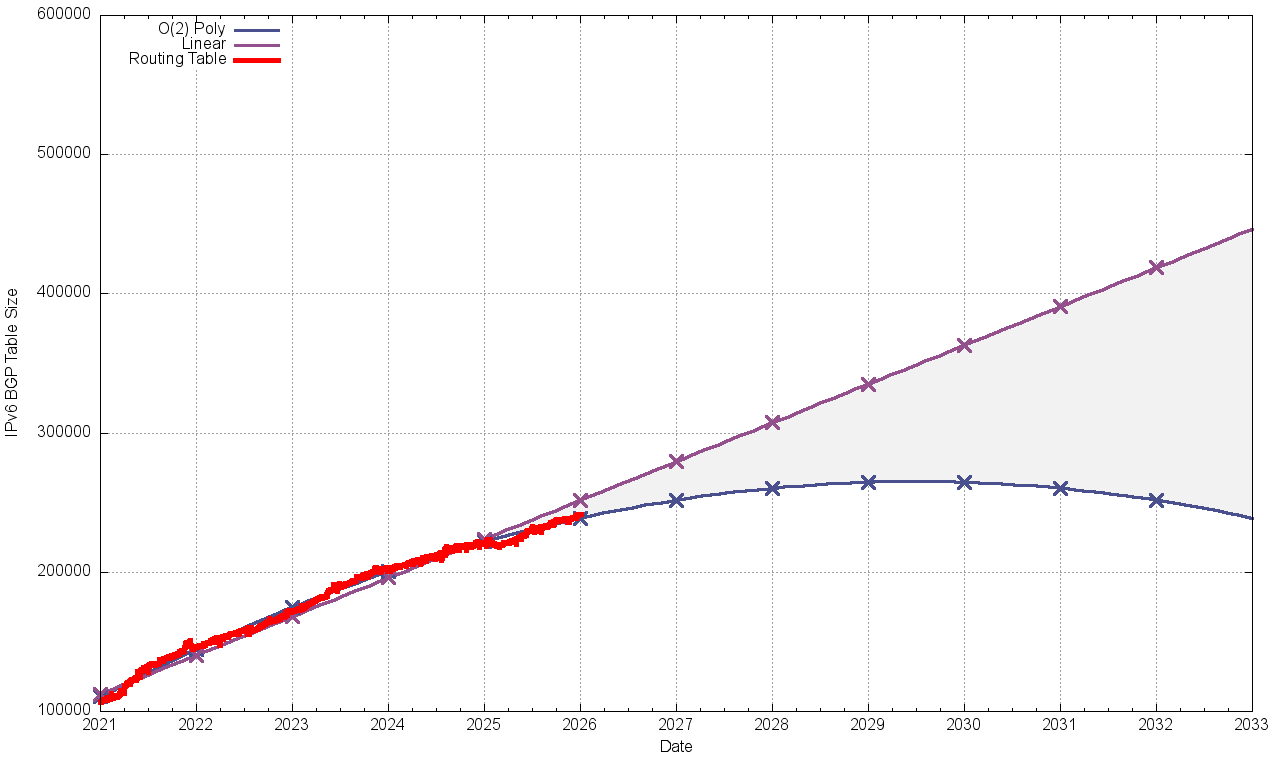

The same technique can be used for the IPv6 routing table. Figure 29 shows the data set for BGP from January 2017 until December 2025, and the application of a least-squares best fit to this data using both linear and O(2) polynomial growth models.

Figure 29 – IIPv6 BGP Table 2021 – 2026 with forward projections

The first order differential, or the rate of growth of the IPv6 BGP routing table is shown in Figure 30. The number of additional routing entries has grown from an average of 10 new entries per day at the start of 2012 to a peak of some 230 new entries per day in May 2021. This number declined through the rest of 2021 and the first half of 2022, down to 50 new entries per day in mid-2022. IPv6 activity picked up for the ensuing 12 months, rising to 150 new entries per day by mid 2023, and then declining back to 50 entries per day by the end of 2023. Through 2024 the rate rose to some 70 new entries per day by mid-year and then fell to 40 by the end of the year. The first 3 months of 2025 saw the IPv6 routing table shrink in size, then move into a positive rate for the rest of the year. Current growth rates are some 50 new entries per day, which is one quarter of the current rate of growth in the IPv4 network (Figure 30).

Figure 30 - First Order Differential of IPv6 BGP Table Size

The polynomial model predicts the IPv6 table will peak in January 2029 with a size of 265,000 entries and then will drop in size thereafter.

The projections for the IPv6 table size are shown in Table 6.

| IPv6 Table | Projection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | O(2) Poly | Exponential | ||

| Jan 2020 | 79,000 | |||

| Jan 2021 | 104,000 | |||

| Jan 2022 | 147,000 | |||

| Jan 2023 | 172,000 | |||

| Jan 2024 | 201,000 | |||

| Jan 2025 | 222,000 | |||

| Jan 2026 | 242,000 | 251,682 | 238,965 | 275,682 |

| Jan 2027 | 279,496 | 251,808 | 330,391 | |

| Jan 2028 | 307,310 | 260,369 | 395,958 | |

| Jan 2029 | 335,200 | 264,665 | 474,772 | |

| Jan 2030 | 363,014 | 264,641 | 568,991 | |

| Jan 2031 | 390,827 | 260,346 | 681,907 | |

| Jan 2032 | 418,641 | 251,770 | 817,233 | |

Table 6 – IPv6 BGP Table Size Prediction

The polynomial and exponential growth projection models appear to me to be somewhat unlikely, in my opinion. The linear growth model provides a reasonable estimate of the high bounds of the growth of the IPv6 BGP routing table in the coming years, and the lower bound is the polynomial model.

The data from the previous five years suggests an accelerating level of growth is extremely unlikely, and a linear growth model is a closer fit to this recent past, and an average growth rate of 27,000 new entries per year is a better fit to this recent data.

Conclusion

These predictions for the routing system are highly uncertain. The correlation between network deployments and routing advertisements has been disrupted by the hiatus in supply of IPv4 addresses, causing more recent deployments to make extensive use of various forms of address sharing technologies, and making fundamental alterations to the architecture of the service model of the Internet.

While a number of access providers and service platforms have made significant progress in public IPv6 deployments for their respective customers, the majority of the Internet user base (some 57% the Internet’s user base) is still exclusively using IPv4 as of the end of 2025 (Figure 32).

Figure 31 -IPv6 Deployment 2012 - 2025

These predictions as to the future profile of the routing environment for IPv4 and IPv6, using extrapolation from historical data, can only go so far in providing a coherent picture for the near-term future. As well as the technical issues relating to the evolution of IP technology and the IPv6 transition there are also broader factors such as the state of the global communications economy and the larger global economy.

Investment in communications infrastructure, as with most other forms of infrastructure investment is not generally a short-term proposition. The major benefits tend to be realised in increased efficiency of economic production, rather than short-term windfall gains from infrastructure investment. This means that short term expedient measures, such as a response to a global pandemic or a rapid escalation of energy prices due to regional conflict, can interrupt infrastructure investment programs. The question behind the recent slowing of the growth in both the IPv4 and IPv6 aspects of the Internet’s routing space is whether this slowdown is due to market saturation in the case of IPv4 or a dissipation of collective market impetus in the case of IPv6, or an interruption due to these short-term exogenous market factors. In the latter case we would expect growth to resume once more when the current global market conditions dissipate, while an underlying condition of market saturation is a more permanent state.

If the concern is that the routing system is growing at a rate that is faster than our collective ability to throw available technology at it, then there is absolutely no serious cause for alarm in the current trends of growth in the routing system. There is no evidence of the imminent collapse of BGP. Far from it!

However, the size of the inter-domain routing table is only one half of the story. The stability of the routing system is also very important, and to complete this look at the routing system in 2025 we will also need to look at the dynamic behaviour of the routing system. The profile of BGP update churn in 2025 is a topic we’ll look at in detail in pour next article.

![]()

Disclaimer

The above views do not necessarily represent the views of the Asia Pacific Network Information Centre.

![]()

About the Author

Geoff Huston AM, B.Sc, M.Sc., is the Chief Scientist at APNIC, the Regional Internet Registry serving the Asia Pacific region.